Saturday, 31 May 2008

Thursday, 29 May 2008

'Melawan Lupa'

Melawan Lupa (We Shall Not Forget) is a compilation of 10 short films by independent Indonesian filmmakers, to mark the 10th anniversary of reformasi in that country. That was, of course, the period when mass protests (often involving undergraduates) managed to topple the Suharto dictatorship.

The site for the compilation is here. It is a mixture of fiction and documentary, as you can see. It has already drawn quite a few responses, including from Malaysians who saw it in Indonesia, as can be read here.

I am thinking of organising a couple of screenings in KL, and inviting some of the directors over.

This will of course make a nice companion piece to my own Malaysian Gods, which is meant to mark the 10th anniversary of our own, much tamer reformasi (which actually bore electoral fruit only this year!).

I shall keep you updated!

Footnote:

Although the trailer for Melawan Lupa is not yet online, here is a short and frisky piece of video art by one of the directors, Anggun Priambodo:

Wednesday, 28 May 2008

What social contract?

Sharing the Nation: Faith, Difference, Power and the State 50 Years After Merdeka by Noraini Othman, Mavis C Puthucheary and Clive S. Kessler (SIRD, 2008, 99 pages).

You have heard about Malaysia’s ‘social contract’ ¬ but you have never seen it. Unlike most contracts, it does not exist in written form. No one even knows the exact wording. But the people who use the phrase seem very sure of its meaning.

This ‘social contract’, when used by UMNO leaders, refers to a deal supposedly struck among leaders of the Alliance in the heady months leading to Merdeka. This deal was supposedly made behind closed doors. We are told, in crude terms, that it means that Malays will continue to have political power forever, in exchange for non-Malays being granted citizenship.

Funnily enough, there is no proof that this was ever the intention of our founding fathers. And even funnier (but maybe not in the haha sense) the term ‘social contract’ was used for the first time only in the 1980s.

Before that, you could say that the bargaining that led to the acknowledgement of the special position of the Malays (Article 153 of the Federal Constitution) was a pragmatic measure that took into account the fact that Malays had been organised socially and politically in the country for much longer than the other major races.

It was also one small sign that the aims of the founding parties of the Alliance were not identical. These parties banded together because they could not have achieved national power so decisively otherwise. It was a fragile coalition glued together by political ambition ¬ the same charge that the Alliance descendents now hurl against Pakatan Rakyat.

Mavis Puthucheary’s opening essay in Sharing the Nation, published to mark our 50th Merdeka, is a clear-eyed indictment of how this mundane and pragmatic measure became a beast that would not stop growing. She shows how the terms of this ‘contract’ are not fixed in stone but have been altered, albeit unilaterally, as when special privileges were extended to the natives of Sabah and Sarawak too. What sort of contract can continue to be valid if the terms keep being changed by only one party?

Yes, the ‘social contract’ has been the subject of much triumphalist ethnic chest-thumping by not only politicians but Malay-centric cultural organisations like Gapena. The ‘special privileges,’ as subsequently enacted in policies like the NEP, are taken as immutable rights in perpetuity rather than (to use Tun Ismail’s analogy) something much closer to a golf handicap. But why on earth should a handicap be a source of pride?

The original social contract of Western political theory refers to a situation where the individual gives up some rights to the state, in exchange for the benefits of being a citizen. But the Malaysian version somehow became a secret deal struck between leaders of ethnic parties.

Abuse of this ‘social contract’ idea has led to people feeling less welcome than they should be. And when people are not welcome, they tend to want to leave. It’s ironic that some of us might feel shock and dismay at the prospect of losing a pile of rocks to Singapore, but nary a twinge that Singaporean universities and corporations are poaching so many of Malaysia’s best and brightest.

“Don’t challenge the social contract!” has been the sabre-rattling cry for the past two decades. The idea is that every little thing that was present in our original Constitution should be preserved as sacred. But these same politicians didn’t get their knickers in a twist when this same Constitution received over 600 amendments in the past half-century. A further irony is that this ‘social contract’ is not even contained explicitly in the Constitution. What gives?

There were many competing interests at play in the pre-Merdeka period. These led to some ambiguities and contradictions relating to the rights and responsibilities of its citizens. But the era of the “gentleman’s agreement” seems to be over. People do not want secret deals (or, worse, secret deals supposedly made by our grandparents’ leaders) but openness. We are no longer feudal subjects but national stake-holders.

Sharing the Nation is a slim book but it packs a wallop. In fact, that if you were paying attention, you would notice that we only talked about the first essay (out of three). If you wanna read the other two, get thee to a bookstore.

(Malay Mail, 28 May 2008).

You have heard about Malaysia’s ‘social contract’ ¬ but you have never seen it. Unlike most contracts, it does not exist in written form. No one even knows the exact wording. But the people who use the phrase seem very sure of its meaning.

This ‘social contract’, when used by UMNO leaders, refers to a deal supposedly struck among leaders of the Alliance in the heady months leading to Merdeka. This deal was supposedly made behind closed doors. We are told, in crude terms, that it means that Malays will continue to have political power forever, in exchange for non-Malays being granted citizenship.

Funnily enough, there is no proof that this was ever the intention of our founding fathers. And even funnier (but maybe not in the haha sense) the term ‘social contract’ was used for the first time only in the 1980s.

Before that, you could say that the bargaining that led to the acknowledgement of the special position of the Malays (Article 153 of the Federal Constitution) was a pragmatic measure that took into account the fact that Malays had been organised socially and politically in the country for much longer than the other major races.

It was also one small sign that the aims of the founding parties of the Alliance were not identical. These parties banded together because they could not have achieved national power so decisively otherwise. It was a fragile coalition glued together by political ambition ¬ the same charge that the Alliance descendents now hurl against Pakatan Rakyat.

Mavis Puthucheary’s opening essay in Sharing the Nation, published to mark our 50th Merdeka, is a clear-eyed indictment of how this mundane and pragmatic measure became a beast that would not stop growing. She shows how the terms of this ‘contract’ are not fixed in stone but have been altered, albeit unilaterally, as when special privileges were extended to the natives of Sabah and Sarawak too. What sort of contract can continue to be valid if the terms keep being changed by only one party?

Yes, the ‘social contract’ has been the subject of much triumphalist ethnic chest-thumping by not only politicians but Malay-centric cultural organisations like Gapena. The ‘special privileges,’ as subsequently enacted in policies like the NEP, are taken as immutable rights in perpetuity rather than (to use Tun Ismail’s analogy) something much closer to a golf handicap. But why on earth should a handicap be a source of pride?

The original social contract of Western political theory refers to a situation where the individual gives up some rights to the state, in exchange for the benefits of being a citizen. But the Malaysian version somehow became a secret deal struck between leaders of ethnic parties.

Abuse of this ‘social contract’ idea has led to people feeling less welcome than they should be. And when people are not welcome, they tend to want to leave. It’s ironic that some of us might feel shock and dismay at the prospect of losing a pile of rocks to Singapore, but nary a twinge that Singaporean universities and corporations are poaching so many of Malaysia’s best and brightest.

“Don’t challenge the social contract!” has been the sabre-rattling cry for the past two decades. The idea is that every little thing that was present in our original Constitution should be preserved as sacred. But these same politicians didn’t get their knickers in a twist when this same Constitution received over 600 amendments in the past half-century. A further irony is that this ‘social contract’ is not even contained explicitly in the Constitution. What gives?

There were many competing interests at play in the pre-Merdeka period. These led to some ambiguities and contradictions relating to the rights and responsibilities of its citizens. But the era of the “gentleman’s agreement” seems to be over. People do not want secret deals (or, worse, secret deals supposedly made by our grandparents’ leaders) but openness. We are no longer feudal subjects but national stake-holders.

Sharing the Nation is a slim book but it packs a wallop. In fact, that if you were paying attention, you would notice that we only talked about the first essay (out of three). If you wanna read the other two, get thee to a bookstore.

(Malay Mail, 28 May 2008).

People who read Malay novels must be a very loving lot

These were the Top 10 Malay fiction best-sellers for the whole of last year, as sold in Popular bookshops:

Biar Rindu Berlalu – Sharifah Abu Salem

Ku Seru Kasihmu – Izzul Izzati

Kasih Seharum Lavender – Eita Ashyta

Atas Nama Cinta – Bikash Nur Idris

Bayangan Rindu – Anis Ayuni

Murni Kasih – Norhayati Berahim

Senafas Rindu – Damya Hanna

Cinta... Tiada Akhirnya – Fauziahn Ashari

Buatmu Kekasih – Aisya Sofea

Bunga-bunga Kemboja – Aina Emir.

Biar Rindu Berlalu – Sharifah Abu Salem

Ku Seru Kasihmu – Izzul Izzati

Kasih Seharum Lavender – Eita Ashyta

Atas Nama Cinta – Bikash Nur Idris

Bayangan Rindu – Anis Ayuni

Murni Kasih – Norhayati Berahim

Senafas Rindu – Damya Hanna

Cinta... Tiada Akhirnya – Fauziahn Ashari

Buatmu Kekasih – Aisya Sofea

Bunga-bunga Kemboja – Aina Emir.

Tuesday, 27 May 2008

Pantun time again

JiGOMorrison asks me as a comment in a post below whether I have read As I Please by Salleh Ben Joned.

Answer: Yes yes.

I read the column religiously in the NST every Wednesday, and re-read selected pieces when they came out in book form.

One of my favourite articles is a two-parter on sensual (even erotic) pantun. (Of course it needs to be a two-parter, to imitate the structure of what Salleh calls "the one truly native and very Malay of the poetic forms"). They were both published in May 1991.

I must admit that these two articles started getting me interested in the pantun; I would not have told a story through 60 of them in Tokyo Magic Hour, over a decade later, otherwise. (Although unlike Saharil I am too dumb to create me own).

I was recently in Penang's Chowrasta second-hand book market, where Shahril Nizam picked up a very cute, old and petite paperback, Malay Pantuns (compiled by AW Hamilton and first published in 1941; this particular edition dates back to 1959). I immediately skimmed through to pick out the more saucy ones.

There was one that Salleh had cited too:

Di mana kuang bertelur?

Di atas lata, di ruang batu

Di mana abang nak tidur?

Di atas dada, di ruang susu!

(Hamilton translation makes it more florid:

Where does the Argus pheasant nest?

Above the falls, in rocky clefts!

Where does the lover seek to rest?

Upon your bosom, 'twixt your breasts!)

The susu theme continues:

Sakit kaki ditikam jeruju

Jeruju ada di dalam paya

Sakit hati memandang susu

Susu ada di dalam kebaya.

(Hamilton's version:

The prickles cause my feet to smart

Sea-holly grows amidst the mire

The sight of breasts enflames my heart,

Beneath a woman's loose attire.)

(Somehow, I don't think that kebaya was all that loose...)

Over the past half-century, Malay literature has become more censorious and less interested in sensuality. But the earthy, elemental sounds of a good pantun still successfully 'mock' solemnity and killjoy piety. As explained explicitly here:

Tetitip di tepi kota

Mari dikayuh sampan pengail

Imam, khatib lagi berdosa

Inikan pula kita yang jahil!

(Hamilton's:

Where barnacles cling to the fort,

Come, let us row a fishing smack.

When priests and scribes in sin are caught,

What chance for us who learning lack?)

Answer: Yes yes.

I read the column religiously in the NST every Wednesday, and re-read selected pieces when they came out in book form.

One of my favourite articles is a two-parter on sensual (even erotic) pantun. (Of course it needs to be a two-parter, to imitate the structure of what Salleh calls "the one truly native and very Malay of the poetic forms"). They were both published in May 1991.

I must admit that these two articles started getting me interested in the pantun; I would not have told a story through 60 of them in Tokyo Magic Hour, over a decade later, otherwise. (Although unlike Saharil I am too dumb to create me own).

I was recently in Penang's Chowrasta second-hand book market, where Shahril Nizam picked up a very cute, old and petite paperback, Malay Pantuns (compiled by AW Hamilton and first published in 1941; this particular edition dates back to 1959). I immediately skimmed through to pick out the more saucy ones.

There was one that Salleh had cited too:

Di mana kuang bertelur?

Di atas lata, di ruang batu

Di mana abang nak tidur?

Di atas dada, di ruang susu!

(Hamilton translation makes it more florid:

Where does the Argus pheasant nest?

Above the falls, in rocky clefts!

Where does the lover seek to rest?

Upon your bosom, 'twixt your breasts!)

The susu theme continues:

Sakit kaki ditikam jeruju

Jeruju ada di dalam paya

Sakit hati memandang susu

Susu ada di dalam kebaya.

(Hamilton's version:

The prickles cause my feet to smart

Sea-holly grows amidst the mire

The sight of breasts enflames my heart,

Beneath a woman's loose attire.)

(Somehow, I don't think that kebaya was all that loose...)

Over the past half-century, Malay literature has become more censorious and less interested in sensuality. But the earthy, elemental sounds of a good pantun still successfully 'mock' solemnity and killjoy piety. As explained explicitly here:

Tetitip di tepi kota

Mari dikayuh sampan pengail

Imam, khatib lagi berdosa

Inikan pula kita yang jahil!

(Hamilton's:

Where barnacles cling to the fort,

Come, let us row a fishing smack.

When priests and scribes in sin are caught,

What chance for us who learning lack?)

Monday, 26 May 2008

One essay in the bag?

I enjoyed this article, A tale of three mosques, in yesterday's Star so much that I emailed the writer, whom I have never met, inviting him to write about the architecture of Putrajaya for NME 2. And he agreed this morning.

I have also been actively seeking a few others and I shall inform thee in good time :-)

I have also been actively seeking a few others and I shall inform thee in good time :-)

Friday, 23 May 2008

Recommended this weekend: VERTIGO

The latest theatre show by Namron is on tonight and tomorrow (8:30pm) and Sunday (3pm) at ASWARA.

You know who Namron is, of course!

I know literally nothing about this show except for the title, but the poster seems to invoke Hitchcock's masterpiece of the same name. As it's one of my favourite movies, I am now doubly chuffed to see what it's all about.

RM10 je. If you are dating a student, the student gets in for RM5. Jom!

You know who Namron is, of course!

I know literally nothing about this show except for the title, but the poster seems to invoke Hitchcock's masterpiece of the same name. As it's one of my favourite movies, I am now doubly chuffed to see what it's all about.

RM10 je. If you are dating a student, the student gets in for RM5. Jom!

Wednesday, 21 May 2008

Samy Vellu’s nightmare

Dari Kuliah ke Jalan Raya: Kisah Sekumpulan Pelajar UKM by S. Arutchelvan (Jerit and SIRD, 2007, 224 pages)

The political parties and organisations of the Malay Left in those pre-Merdeka days still existed within a communal (racialised) framework. This is because they could not see themselves as anything other than Malay. How, then, to create an independent Malay nation when half of the population was not Malay?

There were a few conflicting ideas about how to resolve this. One would be to classify non-Malays as Malays as well. Founder Onn Jaafar didn’t manage to achieve this within his own non-left party UMNO, and so he was forced out. The new government reached a kind of compromise with regards to the other races; this is where the words ‘social contract’ came in. (More on that next week).

And so we find ourselves, many decades after Independence, still held mainly captive by racial parties. A racial party need not necessarily be a racist party, but the temptation is awfully great, wouldn’t you say?

Racialised local discourse filters down even to campus politics. This is not surprising because campus activism is often a training-ground for national politicians.

S. Aruthchelvan entered Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) as an undergraduate in 1987. Officially, no association was allowed to explicitly represent one race. This was due to a ban by the then-Education Minister Anwar Ibrahim, after tense situations erupted two years before that on the issue of dragon dances. (Remember? Well, that’s a different story).

Although not officially racial, student groups still managed to be ethnic-based by using religious and cultural signifiers. This was the situation that greeted the young Arutchelvan and his friends.

Dari Kuliah ke Jalan Raya paints an exciting picture of political intrigue. There are power struggles, accusations of financial abuse, bullying and intimidation, switched and strategic allegiances, boycotts, anonymous campaigning by pigeonhole pamphleteering (this was before email and SMS blasts) – everything except indelible ink! It’s a wonder anyone had time for classes.

Arutchelvan’s political trajectory is also instructive. Initially, he allied himself to a clandestine Indian-based organization. This is after the annual Ponggal celebration dinner organised by his seniors were found to be financially dodgy, with RM5,000 unaccounted for. He was also shocked that the caste system was perpetuated on campus, right down to cooking and study groups. This led to the establishment of GABERKAS (Gerakan Banteras Kasta) (the Caste Elimination Movement).

Doing volunteer tutoring at a poor estate brought Arutchelvan and friends into conflict with MIC president Samy Vellu, or rather his honchos. This is because they refused instructions from local MIC leaders to line up and greet the supremo, who was visiting the neighbouring village. The words thrown at the students: “You’ve forgotten who gave you your scholarships!” That line alone tells a lot about old-school, feudalist politics.

Constant exposure to exploited plantation workers made Arutchelvan realise not only the limits of ethnic politics, but also that merely teaching the kids to pass exams won’t do much to improve their lot. The workers themselves needed the political awareness of how they were being screwed over.

Many more twists and turns later (so many secret meetings!) Arutchelvan became the pro-tem secretary general of Parti Sosialis Malaysia. This is the most hard-core left-wing party in Malaysia and uses a class-based (rather than race-based) approach. Tellingly, while our Registrar of Societies has no qualms about approving all manner of racial parties, the PSM has been refused permission for a decade. The case is still pending in court. What gives?

This is an unusually candid memoir. It names people the author accuses of sabotage or perfidy. It also brims with passion. Written to inspire young activists (and written only after Arutchelvan read Che Guevera’s Bolivian diaries!), it is emphatic, rousing and, if I may be permitted to say, badass. The minutae of small-scale political struggle does lend the occasional note of bathos; there is otherwise not much humour.

Postscript since publication: For the first time, PSM won two seats in the last elections. (But since it is not yet a registered party, the candidates ran under the PKR banner). One of PSM’s guys even ‘slew’ Samy Vellu. Is the old style of politics represented by Samy on the way out? One hopes there are now enough smart youths who realise that ethnic leaders don’t give out scholarships out of their own pockets.

(Malay Mail, 21 May 2008)

The political parties and organisations of the Malay Left in those pre-Merdeka days still existed within a communal (racialised) framework. This is because they could not see themselves as anything other than Malay. How, then, to create an independent Malay nation when half of the population was not Malay?

There were a few conflicting ideas about how to resolve this. One would be to classify non-Malays as Malays as well. Founder Onn Jaafar didn’t manage to achieve this within his own non-left party UMNO, and so he was forced out. The new government reached a kind of compromise with regards to the other races; this is where the words ‘social contract’ came in. (More on that next week).

And so we find ourselves, many decades after Independence, still held mainly captive by racial parties. A racial party need not necessarily be a racist party, but the temptation is awfully great, wouldn’t you say?

Racialised local discourse filters down even to campus politics. This is not surprising because campus activism is often a training-ground for national politicians.

S. Aruthchelvan entered Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) as an undergraduate in 1987. Officially, no association was allowed to explicitly represent one race. This was due to a ban by the then-Education Minister Anwar Ibrahim, after tense situations erupted two years before that on the issue of dragon dances. (Remember? Well, that’s a different story).

Although not officially racial, student groups still managed to be ethnic-based by using religious and cultural signifiers. This was the situation that greeted the young Arutchelvan and his friends.

Dari Kuliah ke Jalan Raya paints an exciting picture of political intrigue. There are power struggles, accusations of financial abuse, bullying and intimidation, switched and strategic allegiances, boycotts, anonymous campaigning by pigeonhole pamphleteering (this was before email and SMS blasts) – everything except indelible ink! It’s a wonder anyone had time for classes.

Arutchelvan’s political trajectory is also instructive. Initially, he allied himself to a clandestine Indian-based organization. This is after the annual Ponggal celebration dinner organised by his seniors were found to be financially dodgy, with RM5,000 unaccounted for. He was also shocked that the caste system was perpetuated on campus, right down to cooking and study groups. This led to the establishment of GABERKAS (Gerakan Banteras Kasta) (the Caste Elimination Movement).

Doing volunteer tutoring at a poor estate brought Arutchelvan and friends into conflict with MIC president Samy Vellu, or rather his honchos. This is because they refused instructions from local MIC leaders to line up and greet the supremo, who was visiting the neighbouring village. The words thrown at the students: “You’ve forgotten who gave you your scholarships!” That line alone tells a lot about old-school, feudalist politics.

Constant exposure to exploited plantation workers made Arutchelvan realise not only the limits of ethnic politics, but also that merely teaching the kids to pass exams won’t do much to improve their lot. The workers themselves needed the political awareness of how they were being screwed over.

Many more twists and turns later (so many secret meetings!) Arutchelvan became the pro-tem secretary general of Parti Sosialis Malaysia. This is the most hard-core left-wing party in Malaysia and uses a class-based (rather than race-based) approach. Tellingly, while our Registrar of Societies has no qualms about approving all manner of racial parties, the PSM has been refused permission for a decade. The case is still pending in court. What gives?

This is an unusually candid memoir. It names people the author accuses of sabotage or perfidy. It also brims with passion. Written to inspire young activists (and written only after Arutchelvan read Che Guevera’s Bolivian diaries!), it is emphatic, rousing and, if I may be permitted to say, badass. The minutae of small-scale political struggle does lend the occasional note of bathos; there is otherwise not much humour.

Postscript since publication: For the first time, PSM won two seats in the last elections. (But since it is not yet a registered party, the candidates ran under the PKR banner). One of PSM’s guys even ‘slew’ Samy Vellu. Is the old style of politics represented by Samy on the way out? One hopes there are now enough smart youths who realise that ethnic leaders don’t give out scholarships out of their own pockets.

(Malay Mail, 21 May 2008)

New word from Lingam report

I just finished reading the main part of the Royal Commission report on the VK Lingam scandal (see Malaysiakini for more info) and I am glad that I learned a new word. Perhaps you know it already:

recuse (v.)/ recusal (n.)

Page 10 alone will give you a strong clue what it means:

All fifty available copies of the report were sold out in half an hour. And the report cost over RM500 each!

Strictly within the confines of its genre, it's quite a badass report and much more entertaining that the government's white paper on the BMF scandal in the 1980s (which I could neither understand nor finish, such a himbo is me). This page (96) is one of my favourites:

The idea of a 'Lingam' being 'emasculated'! Never ever ever let it be said that Malaysia lacks material for satirical fiction.

recuse (v.)/ recusal (n.)

Page 10 alone will give you a strong clue what it means:

All fifty available copies of the report were sold out in half an hour. And the report cost over RM500 each!

Strictly within the confines of its genre, it's quite a badass report and much more entertaining that the government's white paper on the BMF scandal in the 1980s (which I could neither understand nor finish, such a himbo is me). This page (96) is one of my favourites:

The idea of a 'Lingam' being 'emasculated'! Never ever ever let it be said that Malaysia lacks material for satirical fiction.

Sunday, 18 May 2008

Towards a 20th century Malaysian book canon

If you were to compile, say, 50 Malaysian books that you should read, what would this list consist of? The problems of canons are well-known – elitist! subjective! time-bound! – but let's try giving it a go anyway.

Books by foreigners but set in Malay(si)a are included. But each book needs to be somehow important, iconic, worthy of discussion (but you don't need to LIKE it). A good rule of thumb: If you hadn't read the book, you would have at least known enough about it to mention it. (Or: ... you would have at least pretended to have read it).

Let's keep it to the 20th century and rank in alphabetical order of author. A baker's dozen to start with:

A. Samad Said: Salina

Adibah Amin: As I Was Passing (I & II)

Burgess, Anthony: The Malayan Trilogy

Fauconnier, Henri: The Soul of Malaya

Kassim Ahmad: Hadis - Satu Penilaian Semula

Lat: Kampung Boy

Lat: Mat Som

Mahathir Mohamad: The Malay Dilemma

Rehman Rashid: A Malaysian Journey

Shahnon Ahmad: Ranjau Sepanjang Jalan

Shahnon Ahmad: SHIT

Tamar Jalis: Bercakap Dengan Jin

Usman Awang: Puisi-Puisi Pilihan

Books by foreigners but set in Malay(si)a are included. But each book needs to be somehow important, iconic, worthy of discussion (but you don't need to LIKE it). A good rule of thumb: If you hadn't read the book, you would have at least known enough about it to mention it. (Or: ... you would have at least pretended to have read it).

Let's keep it to the 20th century and rank in alphabetical order of author. A baker's dozen to start with:

A. Samad Said: Salina

Adibah Amin: As I Was Passing (I & II)

Burgess, Anthony: The Malayan Trilogy

Fauconnier, Henri: The Soul of Malaya

Kassim Ahmad: Hadis - Satu Penilaian Semula

Lat: Kampung Boy

Lat: Mat Som

Mahathir Mohamad: The Malay Dilemma

Rehman Rashid: A Malaysian Journey

Shahnon Ahmad: Ranjau Sepanjang Jalan

Shahnon Ahmad: SHIT

Tamar Jalis: Bercakap Dengan Jin

Usman Awang: Puisi-Puisi Pilihan

Saturday, 17 May 2008

As seen in Bandar Baru Sentul

Wednesday, 14 May 2008

Woman of the left

Memoir Shamsiah Fakeh: Dari AWAS ke Rejimen ke-10 (SIRD, 142 pages, 2007).

Some books have dramatic histories, just as some people have dramatic lives.

Shamsiah Fakeh’s memoirs were first published in 2004 but then withdrawn from circulation. It was not officially banned, but in Malaysia things do not have to be official to work. Pressure was exerted by the Information Ministry (then headed by the quotable Zainuddin Maidin) on the publisher Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia –and before you can say ‘goblok’, the book could no longer be found, even for ready money.

Why the fuss? Well, Shamsiah is an iconic figure of the Malay Left. Her very presence complicates the idea that the pro-Independence movement was such a simple affair.

She led Angkatan Wanita Sedar (with the cool acronym AWAS), which joined forces with the equally catchy API (Angkatan Pemuda Insaf). These were among the organisations that drew support from the peasantry and nascent intelligentsia rather than the aristocracy, so they were not exactly welcomed with tea and scones by the British.

AWAS was set up in 1946. She and API leader Ahmad Boestamam quickly became known for their fiery speeches throughout Malaya. They got married, even though he already had a wife. But that’s OK – the two women got along fine. A few months later, Boestamam was arrested on sedition charges because of a pro-Independence pamphlet where the words ‘Merdeka dengan darah’ (freedom through blood) were used.

It’s not surprising that the British invoked sedition charges to keep precocious natives down. After all, Malaya was a very lucrative segment of the Empire, and if the locals started thinking for themselves, who could tell what mischief they would get up to? (The corollary of this is that a truly independent nation would not invoke sedition charges so easily!)

The marriage did not last because of interference by his sister. Shamsiah was so upset that she fled from the house when Boestamam failed to defend her. This short-lived marriage was already her third; she does not have kind words about the first two husbands, who sounded like right cads.

AWAS was one of a clutch of leftist organizations that were banned in 1948 at the onset of the Emergency. The options for Shamsiah would be to continue her political life in more pliable associations or to keep resisting actively. She chose the difficult path of going into the jungle with the 10th Regiment, the Malay wing of the Communist Party of Malaya.

Life became even less comfortable. She frequently bungled in the jungle due to her lack of survival skills. She got lost several times and her accounts of these are rich with a very human bathos.

How on earth did this comely Malay woman, who studied in religious school, join up with the communists? The British and Malay establishment spread all kinds of nasty rumours about her. One that has persisted to this day is that she killed her newborn baby because the tyke couldn’t stop crying, and was thus a risk in the jungle hideout. She gives her own account of this incident, and although it absolves her, it will make you shudder.

She and her husband Ibrahim Mohamad were sent to China for further ideological training. But they were later fired by the Communist Party, assaulted and placed under house arrest. Their expulsion arose from squabbling within the CPM, partly as a result of wider clashes between the Chinese and the Soviets, but partly also due to internal frustration at the increasingly futile guerrilla struggle in independent Malaysia. Upon release, she earned her keep in China by working in a steel foundry.

This memoir isn’t as well-researched as, say, Chin Peng’s 527-page doorstopper My Side of History (2003). It is very patchy (especially in the second half) but its chatty, surprisingly good-natured humour shines through. Principled but not help captive by rigid party orthodoxies, she is not bitter about the choices she made.

Shamsiah and her family were allowed to return to Malaysia only in 1994. She is now 84 and not in the best of health; she couldn’t even attend the launch of this revised reprint. The last chapter consists of an interview she gave last year, where she is asked what she thinks of Malaysia. Her answer, where she advocates the abolishment of race-based, class-based and religious-based discrimination, shows that she’s still got it.

(Malay Mail, 14 May 2008)

Some books have dramatic histories, just as some people have dramatic lives.

Shamsiah Fakeh’s memoirs were first published in 2004 but then withdrawn from circulation. It was not officially banned, but in Malaysia things do not have to be official to work. Pressure was exerted by the Information Ministry (then headed by the quotable Zainuddin Maidin) on the publisher Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia –and before you can say ‘goblok’, the book could no longer be found, even for ready money.

Why the fuss? Well, Shamsiah is an iconic figure of the Malay Left. Her very presence complicates the idea that the pro-Independence movement was such a simple affair.

She led Angkatan Wanita Sedar (with the cool acronym AWAS), which joined forces with the equally catchy API (Angkatan Pemuda Insaf). These were among the organisations that drew support from the peasantry and nascent intelligentsia rather than the aristocracy, so they were not exactly welcomed with tea and scones by the British.

AWAS was set up in 1946. She and API leader Ahmad Boestamam quickly became known for their fiery speeches throughout Malaya. They got married, even though he already had a wife. But that’s OK – the two women got along fine. A few months later, Boestamam was arrested on sedition charges because of a pro-Independence pamphlet where the words ‘Merdeka dengan darah’ (freedom through blood) were used.

It’s not surprising that the British invoked sedition charges to keep precocious natives down. After all, Malaya was a very lucrative segment of the Empire, and if the locals started thinking for themselves, who could tell what mischief they would get up to? (The corollary of this is that a truly independent nation would not invoke sedition charges so easily!)

The marriage did not last because of interference by his sister. Shamsiah was so upset that she fled from the house when Boestamam failed to defend her. This short-lived marriage was already her third; she does not have kind words about the first two husbands, who sounded like right cads.

AWAS was one of a clutch of leftist organizations that were banned in 1948 at the onset of the Emergency. The options for Shamsiah would be to continue her political life in more pliable associations or to keep resisting actively. She chose the difficult path of going into the jungle with the 10th Regiment, the Malay wing of the Communist Party of Malaya.

Life became even less comfortable. She frequently bungled in the jungle due to her lack of survival skills. She got lost several times and her accounts of these are rich with a very human bathos.

How on earth did this comely Malay woman, who studied in religious school, join up with the communists? The British and Malay establishment spread all kinds of nasty rumours about her. One that has persisted to this day is that she killed her newborn baby because the tyke couldn’t stop crying, and was thus a risk in the jungle hideout. She gives her own account of this incident, and although it absolves her, it will make you shudder.

She and her husband Ibrahim Mohamad were sent to China for further ideological training. But they were later fired by the Communist Party, assaulted and placed under house arrest. Their expulsion arose from squabbling within the CPM, partly as a result of wider clashes between the Chinese and the Soviets, but partly also due to internal frustration at the increasingly futile guerrilla struggle in independent Malaysia. Upon release, she earned her keep in China by working in a steel foundry.

This memoir isn’t as well-researched as, say, Chin Peng’s 527-page doorstopper My Side of History (2003). It is very patchy (especially in the second half) but its chatty, surprisingly good-natured humour shines through. Principled but not help captive by rigid party orthodoxies, she is not bitter about the choices she made.

Shamsiah and her family were allowed to return to Malaysia only in 1994. She is now 84 and not in the best of health; she couldn’t even attend the launch of this revised reprint. The last chapter consists of an interview she gave last year, where she is asked what she thinks of Malaysia. Her answer, where she advocates the abolishment of race-based, class-based and religious-based discrimination, shows that she’s still got it.

(Malay Mail, 14 May 2008)

Friday, 9 May 2008

To the left, to the left

Social Roots of the Malay Left by Rustam A. Sani (SIRD, 80 pages, 2008)

The copyright page of a book is not usually a source of pathos. But this slim volume is an unhappy exception, as the author is listed as “Rustam A Sani, 1944 – “. The unfortunate story this conceals is that the writer died just a few days after the book came back from the printer. Subsequent editions will, I trust, add the year 2008 for necessary closure.

Rustam had been one of Malaysia’s leading public intellectuals for some time. I used to follow his Utusan Malaysia column in the 1990s before it became a casualty of those heady ‘Mahathir vs Anwar’ days. (Which is not to say that those days are over).

Many of those pieces were later collected in the book Menjelang Reformasi (2004), which critiqued various aspects of the Mahathir administration. His phrase ‘illiberal democracy’ to describe Malaysian governance seems imperishable.

Unlike Hishamuddin Rais (whom we discussed earlier), Rustam’s voice is not slangy or hip. But this doesn’t mean boring, as his measured tone can also include its own style of sarcasm. His background in sociology also gave him an ability to analyse hot-button issues in the wider context of our people, history and environment.

Although touted as a new book, Social Roots of the Malay Left is actually his 1975 Masters thesis. It’s also very specific: You get what the title promises and not much more.

Despite its specificity, this book will make you happy. No, it won’t help you generate wealth, find true love or get a better body. But it will make you see that our history is not nearly as boring as you have been led to believe. And for that alone, gratitude is in order.

They say that history is written by the victors and, whadda ya know, they were right again! Watching the 50th Merdeka countdown last year, you may have thought that our national narrative was a linear and uncomplicated one in which UMNO was simply responsible for everything. Even the party slogan dulu, kini dan selamanya (then, now and forever) is reminiscent of some boyband line that speaks of perpetual, selfless devotion. But like most boyband lyrics, it should be taken with a fair-sized bowl of salt.

Rustam starts off by saying that we should discard the conventional Western definition of ‘Left’. There is no evidence to suggest that the protagonists of this book spent all their time worrying about how best to apply the writings of Marx or Trotsky to the nation.

Instead, ‘Left’ should be understood within the communal politics that characterised our society. The protagonists here, such as the founders of Kesatuan Melayu Muda (the first party to call for independence) were ‘Left’ in the sense that they did not come from the ranks of nobility. They were, instead, teachers and journalists. So this is why the roots of the movement can best be understood in social rather than purely ideological terms.

Some folks were even prepared to take up arms and cooperate with the more radical elements of the Communist Party of Malaya (the nation’s first political party). This is why Malay leftists were seen as a bigger threat than the ‘negotiating table’ style of UMNO, and why many were placed behind bars.

An interesting point raised here is that Malay literature became ‘defeudalised’ within one generation. Fictional stories used to be about kings but by the 1950s they were all about commoners. But in Malay politics, particularly of the ‘Right’, feudal sentiments still persist.

There’s also a thrilling bit of drama here where Rustam disputes an analysis offered by his father Ahmad Boestamam (without revealing the family connection) relating to the continuity between two early parties. It’s not quite Oedipal but it livens things up considerably.

A few sentences appear to have been altered since 1975 – chiefly his characterisation of Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) as a descendent of Malay leftist parties. Some hard-core socialists may scoff at this description. But, at the very least, the multiracial nature of PKR points the way to a more inclusive brand of politics.

Which brings us to the question that Rustam has pondered elsewhere: How do we now transform Malay nationalism into Malaysian nationalism?

(Malay Mail, 9 May 2008).

The copyright page of a book is not usually a source of pathos. But this slim volume is an unhappy exception, as the author is listed as “Rustam A Sani, 1944 – “. The unfortunate story this conceals is that the writer died just a few days after the book came back from the printer. Subsequent editions will, I trust, add the year 2008 for necessary closure.

Rustam had been one of Malaysia’s leading public intellectuals for some time. I used to follow his Utusan Malaysia column in the 1990s before it became a casualty of those heady ‘Mahathir vs Anwar’ days. (Which is not to say that those days are over).

Many of those pieces were later collected in the book Menjelang Reformasi (2004), which critiqued various aspects of the Mahathir administration. His phrase ‘illiberal democracy’ to describe Malaysian governance seems imperishable.

Unlike Hishamuddin Rais (whom we discussed earlier), Rustam’s voice is not slangy or hip. But this doesn’t mean boring, as his measured tone can also include its own style of sarcasm. His background in sociology also gave him an ability to analyse hot-button issues in the wider context of our people, history and environment.

Although touted as a new book, Social Roots of the Malay Left is actually his 1975 Masters thesis. It’s also very specific: You get what the title promises and not much more.

Despite its specificity, this book will make you happy. No, it won’t help you generate wealth, find true love or get a better body. But it will make you see that our history is not nearly as boring as you have been led to believe. And for that alone, gratitude is in order.

They say that history is written by the victors and, whadda ya know, they were right again! Watching the 50th Merdeka countdown last year, you may have thought that our national narrative was a linear and uncomplicated one in which UMNO was simply responsible for everything. Even the party slogan dulu, kini dan selamanya (then, now and forever) is reminiscent of some boyband line that speaks of perpetual, selfless devotion. But like most boyband lyrics, it should be taken with a fair-sized bowl of salt.

Rustam starts off by saying that we should discard the conventional Western definition of ‘Left’. There is no evidence to suggest that the protagonists of this book spent all their time worrying about how best to apply the writings of Marx or Trotsky to the nation.

Instead, ‘Left’ should be understood within the communal politics that characterised our society. The protagonists here, such as the founders of Kesatuan Melayu Muda (the first party to call for independence) were ‘Left’ in the sense that they did not come from the ranks of nobility. They were, instead, teachers and journalists. So this is why the roots of the movement can best be understood in social rather than purely ideological terms.

Some folks were even prepared to take up arms and cooperate with the more radical elements of the Communist Party of Malaya (the nation’s first political party). This is why Malay leftists were seen as a bigger threat than the ‘negotiating table’ style of UMNO, and why many were placed behind bars.

An interesting point raised here is that Malay literature became ‘defeudalised’ within one generation. Fictional stories used to be about kings but by the 1950s they were all about commoners. But in Malay politics, particularly of the ‘Right’, feudal sentiments still persist.

There’s also a thrilling bit of drama here where Rustam disputes an analysis offered by his father Ahmad Boestamam (without revealing the family connection) relating to the continuity between two early parties. It’s not quite Oedipal but it livens things up considerably.

A few sentences appear to have been altered since 1975 – chiefly his characterisation of Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) as a descendent of Malay leftist parties. Some hard-core socialists may scoff at this description. But, at the very least, the multiracial nature of PKR points the way to a more inclusive brand of politics.

Which brings us to the question that Rustam has pondered elsewhere: How do we now transform Malay nationalism into Malaysian nationalism?

(Malay Mail, 9 May 2008).

Wednesday, 7 May 2008

# 1 / 60

Today I will begin my new weekly column in Malay Mail (the revamp seems to have removed 'The' from the paper's name). This will be my first time writing for this paper.

It's called Pulp Friction, and I will devote each article to one local book. Most of the books will be new but some will be older, including some out-of-print titles. The column is meant to flow from one book to another.

I was inspired to do this after reading Nick Hornby's "Stuff I've Been Reading" column in The Believer magazine.

The idea is to get around 60 pieces, which will then be rewritten slightly and reformatted as a book! Just like Nick (he seems so matey so I will just call him Nick) did with The Polysyllabic Spree. I will need to find another publisher for this, as Matahari Books does not republish newspaper columns, so there.

The first piece:

More fun than Ziana Zain

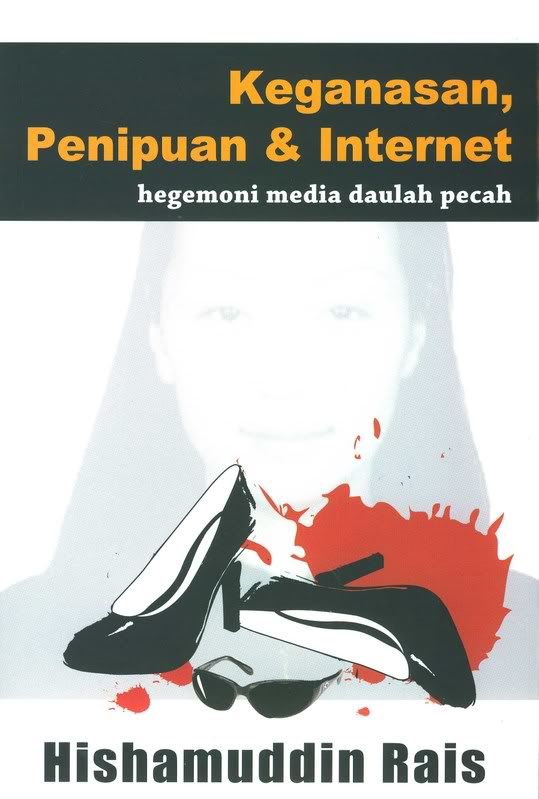

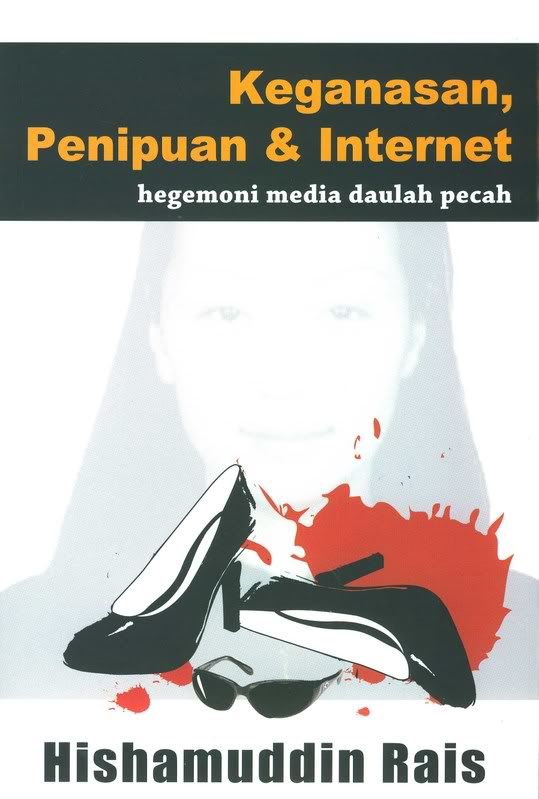

Keganasan, Penipuan & Internet: Hegemoni Media Daulah Pecah

By Hishamuddin Rais (SIRD, 292 pages, 2008).

The name Ziana Zain pops up quite a few times in this new book by Hishamuddin Rais. She doesn’t appear on the cover, though. That honour is reserved for an inadvertently famous Mongolian named Altantuya.

The juxtaposition of the sultry chanteuse and the tragic model/interpreter is enough to give a clue as to the contents of Keganasan, Penipuan & Internet. It looks at current issues (most often political) through an accessible, even pop, gaze. The sub-title adds that the State’s media hegemony has been broken. (So now you know what daulah means!)

Although the pieces were written before the March 8, they offer a refreshing primer on the public groundswell of discontent that the Barisan Nasional government ignored at its own peril. The trouble with the BN is that it started to believe its own hype, as churned out by its mostly docile print and electronic media. And Hishamuddin’s columns here appeared not in the mainstream Malay or English press but Oriental Daily, Suara Keadilan and Malaysia Today.

BN’s arrogant incumbency was ample fodder for a satirist and libertarian hipster like Hishamuddin, as the nightly news becomes a rich source of comedy. And he often takes things further than others would. For example, while conservatives and liberals wrestled over just how ‘offensive’ the Negarakuku music video was, he gleefully points out that our national anthem is itself copied from foreigners. (For added measure, he wants us to know that our flag is, too).

Rather than make piecemeal suggestions on how the government can improve (which is what most of our captive liberal columnists would timorously do) he opines that the whole system itself is rotten. If it cannot even acknowledge how our nation was built (on the blood of leftist fighters), then what hope does this Establishment have of survival? More to the point: Is its continued survival such a good thing?

But his targets aren’t confined to corruption scandals and official doublespeak: the ‘monkey see, monkey do’ noveaux riche pretensions of Malaysian, particularly Malay, society are also a gift that keeps on giving.

Hishamuddin is known as a former ISA detainee and former filmmaker, although these two facts are absent from his three-paragraph bio. More to the point would be his activities as a campus student leader in the early 1970s, before the University and University Colleges Act (UCCA) robbed student radicalism of its cojones. He fled the country for two decades following a government clampdown.

Hishamuddin’s politics are progressive and secular. Whenever he uses the word ‘we’, you can be sure he speaks not of the ruling or even liberal elite but of the street-level throb he experiences around him. There are very few Malay-language columnists like him, since he does not hide behind religious platitudes or academic bamboozling. There are, to be sure, atavistic echoes of Pak Sako and Salleh Ben Joned, who knew how to be earthy and jokey even when serious.

He is pithy, sarcastic, anecdotal: in Freudian terms he is a raging Id.

There are times when this becomes a problem. His championing of counter-cultural sources leads him to some dodgy places, such as giving the 911 conspiracy theorists credit for being far more respected than they are.

The phrase ‘champagne socialist’ is normally a putdown for bleeding-heart liberals who don’t have to sacrifice anything, but he wants to show that, if one is not too tied to dogma, it is possible to partake of both socialism and champagne as parts of a consistent lived philosophy of democratic enjoyment.

On the minus side: Like many Malaysian books, it’s actually a compilation of opinion pieces published over the years. Hishamuddin takes a dig at Ungku Aziz for never having written a real book, so I hope he can do better someday.

There are also more typographical errors than the norm. Some of it’s quite charming, because the writer still evidently uses old-fashioned Malay spelling, but if only it were used consistently …

Finally, this non-fiction book needs an Index. In this case the Index would contain items such as Firaun (look under: Mahathir) and of course Ziana Zain, She would be sandwiched somewhere between Zainuddin Maidin and zombie, which is not exactly where any kind of girl would like to be – and I don’t care how progressive she is.

(Malay Mail, 7 May 2008).

It's called Pulp Friction, and I will devote each article to one local book. Most of the books will be new but some will be older, including some out-of-print titles. The column is meant to flow from one book to another.

I was inspired to do this after reading Nick Hornby's "Stuff I've Been Reading" column in The Believer magazine.

The idea is to get around 60 pieces, which will then be rewritten slightly and reformatted as a book! Just like Nick (he seems so matey so I will just call him Nick) did with The Polysyllabic Spree. I will need to find another publisher for this, as Matahari Books does not republish newspaper columns, so there.

The first piece:

More fun than Ziana Zain

Keganasan, Penipuan & Internet: Hegemoni Media Daulah Pecah

By Hishamuddin Rais (SIRD, 292 pages, 2008).

The name Ziana Zain pops up quite a few times in this new book by Hishamuddin Rais. She doesn’t appear on the cover, though. That honour is reserved for an inadvertently famous Mongolian named Altantuya.

The juxtaposition of the sultry chanteuse and the tragic model/interpreter is enough to give a clue as to the contents of Keganasan, Penipuan & Internet. It looks at current issues (most often political) through an accessible, even pop, gaze. The sub-title adds that the State’s media hegemony has been broken. (So now you know what daulah means!)

Although the pieces were written before the March 8, they offer a refreshing primer on the public groundswell of discontent that the Barisan Nasional government ignored at its own peril. The trouble with the BN is that it started to believe its own hype, as churned out by its mostly docile print and electronic media. And Hishamuddin’s columns here appeared not in the mainstream Malay or English press but Oriental Daily, Suara Keadilan and Malaysia Today.

BN’s arrogant incumbency was ample fodder for a satirist and libertarian hipster like Hishamuddin, as the nightly news becomes a rich source of comedy. And he often takes things further than others would. For example, while conservatives and liberals wrestled over just how ‘offensive’ the Negarakuku music video was, he gleefully points out that our national anthem is itself copied from foreigners. (For added measure, he wants us to know that our flag is, too).

Rather than make piecemeal suggestions on how the government can improve (which is what most of our captive liberal columnists would timorously do) he opines that the whole system itself is rotten. If it cannot even acknowledge how our nation was built (on the blood of leftist fighters), then what hope does this Establishment have of survival? More to the point: Is its continued survival such a good thing?

But his targets aren’t confined to corruption scandals and official doublespeak: the ‘monkey see, monkey do’ noveaux riche pretensions of Malaysian, particularly Malay, society are also a gift that keeps on giving.

Hishamuddin is known as a former ISA detainee and former filmmaker, although these two facts are absent from his three-paragraph bio. More to the point would be his activities as a campus student leader in the early 1970s, before the University and University Colleges Act (UCCA) robbed student radicalism of its cojones. He fled the country for two decades following a government clampdown.

Hishamuddin’s politics are progressive and secular. Whenever he uses the word ‘we’, you can be sure he speaks not of the ruling or even liberal elite but of the street-level throb he experiences around him. There are very few Malay-language columnists like him, since he does not hide behind religious platitudes or academic bamboozling. There are, to be sure, atavistic echoes of Pak Sako and Salleh Ben Joned, who knew how to be earthy and jokey even when serious.

He is pithy, sarcastic, anecdotal: in Freudian terms he is a raging Id.

There are times when this becomes a problem. His championing of counter-cultural sources leads him to some dodgy places, such as giving the 911 conspiracy theorists credit for being far more respected than they are.

The phrase ‘champagne socialist’ is normally a putdown for bleeding-heart liberals who don’t have to sacrifice anything, but he wants to show that, if one is not too tied to dogma, it is possible to partake of both socialism and champagne as parts of a consistent lived philosophy of democratic enjoyment.

On the minus side: Like many Malaysian books, it’s actually a compilation of opinion pieces published over the years. Hishamuddin takes a dig at Ungku Aziz for never having written a real book, so I hope he can do better someday.

There are also more typographical errors than the norm. Some of it’s quite charming, because the writer still evidently uses old-fashioned Malay spelling, but if only it were used consistently …

Finally, this non-fiction book needs an Index. In this case the Index would contain items such as Firaun (look under: Mahathir) and of course Ziana Zain, She would be sandwiched somewhere between Zainuddin Maidin and zombie, which is not exactly where any kind of girl would like to be – and I don’t care how progressive she is.

(Malay Mail, 7 May 2008).

Monday, 5 May 2008

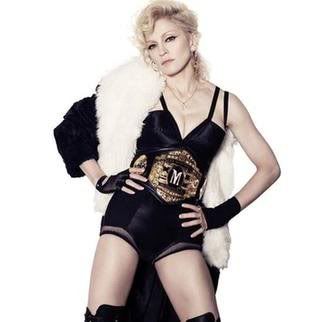

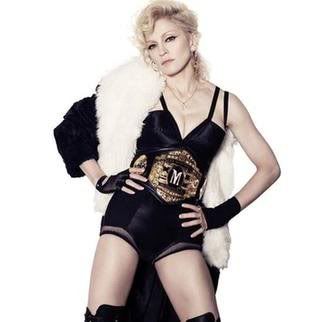

Madonna's disappearing cleavage

I enjoyed flipping through the newly launched Malay Mail today, but reaching page 35 made me realise something was missing:

Madonna's boobs!

This is what a scanned photo from the page looks like:

And this is the actual photo from her CD:

Just a few hours after we celebrated World Press Freedom Day, I am shocked, *shocked* that the Malaysian media is still in shackles. No wonder we are ranked only #124 in that global press-freedom thingy. I hope the various NGOs who issue all those press releases (you know who you are!) will get furiously typing.

True, not everyone is a fan of the photographs adorning this CD (a young Canadian friend of mine said he felt "scared and confused") but there's no denying Madonna is old enough to decide these things. It's the principle that counts, damnit!

Remember folks: If they can do this to a famous anatomical part of an international celeb, just think of what they could do to YOUR bits someday. So look at the photos again, and be afraid. Mwahahaha!

Madonna's boobs!

This is what a scanned photo from the page looks like:

And this is the actual photo from her CD:

Just a few hours after we celebrated World Press Freedom Day, I am shocked, *shocked* that the Malaysian media is still in shackles. No wonder we are ranked only #124 in that global press-freedom thingy. I hope the various NGOs who issue all those press releases (you know who you are!) will get furiously typing.

True, not everyone is a fan of the photographs adorning this CD (a young Canadian friend of mine said he felt "scared and confused") but there's no denying Madonna is old enough to decide these things. It's the principle that counts, damnit!

Remember folks: If they can do this to a famous anatomical part of an international celeb, just think of what they could do to YOUR bits someday. So look at the photos again, and be afraid. Mwahahaha!

Thank you banget!

(photo by Dina Zaman)

(photo by Dina Zaman)Thanks to the estimated 1,200 of you who came to the KLAB over the weekend!

All in all, we sold over RM25,000 worth of books and it's safe to say that several friends were made.

Highlights for me: Meeting, for the first time, Lyna Usman (with whom I shared a booth); publisher Ezra Zaid of ZI; and the graphic artist-writer-filmmaker Chin Yew. Somehow I think I will continue to keep in touch with all three of them.

Lowlight: Getting interviewed by a certifiable bimbo from the mainstream press. She had the nerve to say she "received the press release but didn't read it" and expected me to rehash everything verbally. She didn't look like she'd ever picked up her book in her life and thus showed no interest in any of the titles there. No wonder her newspaper has seen far better days.

Ah well. But I digress.

Some stalls were giving out books for free. Kakiseni did that with its book of prize-winning short plays and all 300 copies they brought were snapped up by people who were patient enough to fill out the 6-page (!) questionnaire that was the prerequisite for ownership.

Special thanks must go to my co-organiser Zulhabri Supian and publicist Dina Zaman, as well as Chet Chin for manning the Book Giveaway stall so efficiently, and Uzair Sawal (check his blog for pictures of the rock kangkang devotees right outside our door) for being such a help all around.

Zulhabri and I will meet tomorrow for a 'post-mortem' but we are definitely psyched about making this an annual affair.

Other, more comprehensive accounts of KLAB can be found via Sharon Bakar & Walski & Fadz.

Thursday, 1 May 2008

The gospel according to Hishamuddin Rais

Saya memilih untuk menulis dalam Bahasa Melayu ... Saya percaya Bahasa Melayu adalah bahasa strategik untuk perubahan. Saya menolak konsep bahasa kebangsaan. Untuk saya 'kebangsaan' tidak memiliki apa-apa nilai.

Kemerosotan sistem pentadbiran negara di bawah United Malay National Organisation begitu terselah. Ini bukan bangkai gajah yang ditutup dengan nyiru tetapi lebih jelas dari itu - seperti Datin Seri Rosmah menunggang gajah.

Bayangkan Mahathir Mohamad terperanjat kerana ada rasuah dalam United Malay National Organisation. Apa punya manusia yang boleh terperanjat apabila mendapat tahu bahawa adanya rasuah dalam partinya, yang dia sendiri pernah menjadi ketua. Terperanjat? Ini samalah seperti cerita Siti Nurhaliza terperanjat apabila melihat Datuk K menanggalkan seluar dalamnya ketika hendak masuk bilik mandi di Hawaii.

Datuk moyang kita telah meninggalkan pesan - jika jumpa ular dan jumpa ayam hutan, ketuk kepala Mahathir dulu.

Pandangan orang ramai tidak akan membantu menyelesaikan bil telefon saya.

Reformasi bukan satu parti politik. Ianya juga bukan satu kelab sosial. Sesiapa sahaja boleh masuk dan keluar. Gerakan Reformasi tidak ada keahlian yang memastikan kesetiaan dengan membayar yuran. Apa yang penting ialah menyokong agenda perjuangan untuk menegakkan sebuah negara yang lebih adil dan lebih telus dari apa yang ada hari ini.

Tolong jangan harap-harapkan pagar. Pagar sekarang bukan sahaja sedang makan padi malah jerami kering dan pokok kelapa di tepi sawah pun sedang dibaham.

Lebih baik orang jahat yang terbukti jahatnya terus berkuasa kerana rakyat secara umum telah mengenalinya. Amat susah untuk melahirkan pertentangan tajam jika 'penyapu' baru datang. 'Penyapu' baru ini akan memberi harapan untuk membersihkan lantai, walhal yang kita mahukan bukan lantai bersih tetapi sebuah rumah yang baru.

Anak muda yang tidak melakukan kesalahan atau kesilapan adalah anak muda yang telah dituakan.

Hidup ini satu pesta yang wajib kita rayakan di setiap detik, bukan hanya permulaan kalendar Gregorian. Champagne dan air anggur kehidupan wajib diminum di setiap saat.

Burung punai saya adalah milik peribadi. Terpulanglah kepada saya dengan siapa saya ingin berkongsi burung punai ini.

All quotes from the book that is available here and in major bookstores nationwide.

All quotes from the book that is available here and in major bookstores nationwide.

Kemerosotan sistem pentadbiran negara di bawah United Malay National Organisation begitu terselah. Ini bukan bangkai gajah yang ditutup dengan nyiru tetapi lebih jelas dari itu - seperti Datin Seri Rosmah menunggang gajah.

Bayangkan Mahathir Mohamad terperanjat kerana ada rasuah dalam United Malay National Organisation. Apa punya manusia yang boleh terperanjat apabila mendapat tahu bahawa adanya rasuah dalam partinya, yang dia sendiri pernah menjadi ketua. Terperanjat? Ini samalah seperti cerita Siti Nurhaliza terperanjat apabila melihat Datuk K menanggalkan seluar dalamnya ketika hendak masuk bilik mandi di Hawaii.

Datuk moyang kita telah meninggalkan pesan - jika jumpa ular dan jumpa ayam hutan, ketuk kepala Mahathir dulu.

Pandangan orang ramai tidak akan membantu menyelesaikan bil telefon saya.

Reformasi bukan satu parti politik. Ianya juga bukan satu kelab sosial. Sesiapa sahaja boleh masuk dan keluar. Gerakan Reformasi tidak ada keahlian yang memastikan kesetiaan dengan membayar yuran. Apa yang penting ialah menyokong agenda perjuangan untuk menegakkan sebuah negara yang lebih adil dan lebih telus dari apa yang ada hari ini.

Tolong jangan harap-harapkan pagar. Pagar sekarang bukan sahaja sedang makan padi malah jerami kering dan pokok kelapa di tepi sawah pun sedang dibaham.

Lebih baik orang jahat yang terbukti jahatnya terus berkuasa kerana rakyat secara umum telah mengenalinya. Amat susah untuk melahirkan pertentangan tajam jika 'penyapu' baru datang. 'Penyapu' baru ini akan memberi harapan untuk membersihkan lantai, walhal yang kita mahukan bukan lantai bersih tetapi sebuah rumah yang baru.

Anak muda yang tidak melakukan kesalahan atau kesilapan adalah anak muda yang telah dituakan.

Hidup ini satu pesta yang wajib kita rayakan di setiap detik, bukan hanya permulaan kalendar Gregorian. Champagne dan air anggur kehidupan wajib diminum di setiap saat.

Burung punai saya adalah milik peribadi. Terpulanglah kepada saya dengan siapa saya ingin berkongsi burung punai ini.

All quotes from the book that is available here and in major bookstores nationwide.

All quotes from the book that is available here and in major bookstores nationwide.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)