Good Neighbours: The Art of Adibah Amin

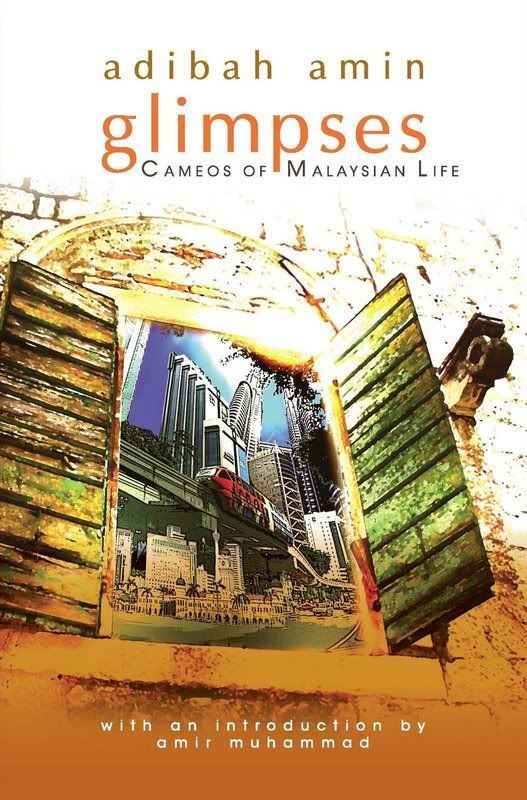

If you are a Malaysian who is picking up this book, chances are you will be familiar with Adibah Amin’s recently reissued, two-volume As I Was Passing, first published as newspaper columns in the 1970s. If so, you will certainly need no further encouragement – from me or anyone else – to get your grubby mitts on Glimpses.

The articles here were written more than a decade after As I Was Passing, and although Adibah’s inimitable wit and warmth continue to shine through, there are greater hints that things are not going so well with the Malaysian project.

The multicultural ease of Malaysians as recorded in As I Was Passing seems to be under threat, due to increasingly entrenched communal sentiments. Racial jokes that used to be taken in good fun by one and all now have a darker undertow. (It has been said that Malaysians are becoming more sensitive, but the opposite is true: We are becoming more insensitive).

What happened in the meantime? Perhaps the capitalist short-cuts of the 1980s put too much emphasis on physical monuments, brushing aside intangible but arguably more important things. But once we have bolted out the door, is it still possible to go back and retrieve what we forgot?

It is a measure of Adibah’s moral strength that she neither sweeps these problems under the carpet nor seeks escape into an unreconstructed nostalgia based on an idyllic past. Although she notes that Malaysians seem to be getting further apart (and drawn together mainly on food-laden occasions such as festive holidays) she is well aware of the structural inequalities that have given rise to this. These inequalities ¬– and attendant insensitivities – are at the root cause of the polarisation that she laments.

Adibah is able to put herself into the footwear – be it the leather sandals, terompah or humble selipar Jepun – of others. This is not as easy an accomplishment as it sounds, especially in a society where you can get very far by playing your racial or religious card. A demagogue would see the rights and even basic existence of the Other as a threat. Adibah is the opposite of a demagogue.

The level of empathy she displays could only have come about through a keen intelligence, instinctive curiosity and a firm sense of fair play. Her pride in our imagined community isn’t of the obnoxious bragging variety; we all know that bragging is a sign of insecurity, anyway. She continues to have hope because she has met some very good people, and knows that there are many more out there. And goodness has certainly never been the monopoly of any particular group of people.

To pick just one seemingly innocuous example: Her essay on some neighbours she has known sneaks in the word ‘temples’, the sole indication that the family she’s speaking of must be from a different faith. Nowadays, when temples (or mosques, or churches) became part of public discussion, they would just as likely become signifiers in the contested terrain of ‘our rights’ versus ‘their rights.’ And how many of us now would fail to foreground a person’s creed the moment we refer to him or her? But Adibah concentrates, with sly wit, on the more important qualities – such as the simple ability to return borrowed items! – that a good neighbour should possess.

A particularly striking essay, one of the longest here, is on the implications of Merdeka. Read in the context of our national orgy of self-congratulation (which often became the exclusive channel for the political elite to promote and perpetuate its hegemonic legacy), it shines like a star in a fog-filled sky. How many writers could point out that there are many other political fighters, particularly of the leftist variety, that have been forgotten? Or to mention the perception (perhaps silenced now) that our Independence was a relatively painless and contingent one compared to what our neighbours can boast of? Or, perhaps more importantly, to listen to what the young, seemingly apolitical, voices have to say without hectoring them into submission? That she can accomplish all this and more, while never seeming to have an axe to grind, is testament enough to her artistry.

Part of this artistry is the ability to render ideas in concrete, personal terms. In recognizing the integrity of the whistle-blowing schoolgirl in the case of the leaked exam papers, she invites us to ponder the bigger implications of living in a time when we often ‘close one eye’ to corruption. And her unusually intimate account of the breakdown of a relationship due to the man’s surprising (to the woman) reliance on patriarchal power tropes strikes you in the heart. Self-deprecating but no pushover, she knows when something’s amiss.

Fifty years after our much-vaunted Merdeka, there are precious few writers who have managed to achieve the pan-national appeal of Lat, P. Ramlee or Sudirman. Adibah would seem to be the fittest candidate: her unassuming demeanour, transparent prose and disarming humour are for keeps.

Humour, oh yes! Although this Introduction is sadly free of them, the book itself is full of jokes, trust me. I laughed many times – and so will you, unless you are a really uptight type, in which case you are better off reading one of those ‘How to be a millionaire or die trying’ things that will be abundant in the bookshop where you picked this up.

Her humour is often pointed but never cynical. If a cynic is one who knows “the price of everything and the value of nothing” (who said this? what do I look like, the Google page?) then Adibah is empathically not a cynic. She ain’t too impressed by price-tags, but she knows what truly matters – and even if you were broke, her “love don’t cost a thing” (to quote a slightly different Western icon).

If we had more neighbours like Adibah, none of us will ever think of moving away.

2 comments:

mark twain, yeah it is;price of everything, value of nothing

No lah, it's Oscar Wilde.

Post a Comment