Monday, 29 September 2008

Sunday, 28 September 2008

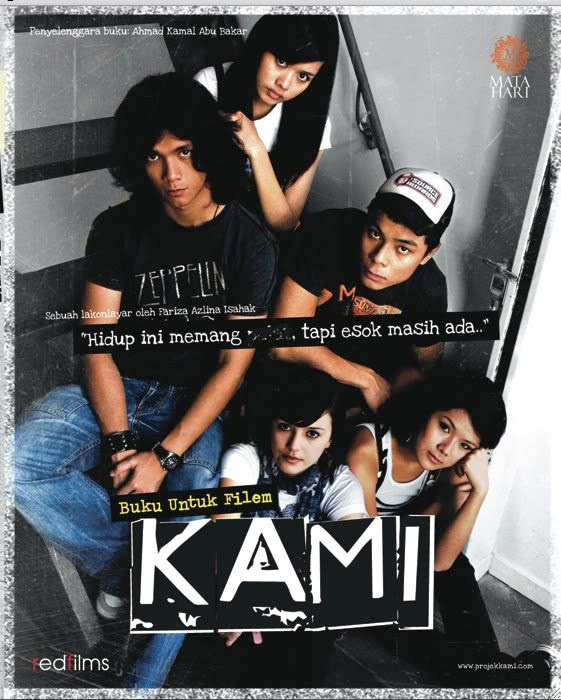

Buku Untuk Filem, why ah?

A journalist who turned up last night asked a few obvious questions ("What is this event? What is this book? What is in it?" - all while holding a copy of said book) but she also asked why I thought of publishing it.

Well...

Way back in the last century, I was a Law student. On impulse, I took a few Film Studies classes because the university allowed me to do so. Lo, my Film grades ended up higher than what I got for Law!

My three years at university were when I learned the most about film. And one of the hallmarks of that era was that I would buy screenplay books of films I liked. Of course, we are talking about the last century here, so the films were Reservoir Dogs, Fargo, Sex Lies and Videotape dan yang sewaktu dengannya. I would often buy them second-hand and eschew the ones with too many glossy colour pictures.

Although I am too lazy and non-discriminating to be a real cinephile, those books did help me to know the films better, and to see filmmaking as something I might conceivably do.

When I was based at Indonesia's Miles Films for half of 2004, I was also pleased to see that this company actively published the screenplays of its own films, such as Ada Apa Dengan Cinta? and Eliana, Eliana.

So although, yes, it's part of merchandising and will hardly change the world, Buku Untuk Filem is a series I started because it will help us to know some movies better. And that's surely one of the ways that we can make other, interesting movies later.

The next one after KAMI will be for the film ESTET, written and directed by Mamat Khalid; the book will be edited by Ajami Hashim. It should be out early next year, God willing.

Well...

Way back in the last century, I was a Law student. On impulse, I took a few Film Studies classes because the university allowed me to do so. Lo, my Film grades ended up higher than what I got for Law!

My three years at university were when I learned the most about film. And one of the hallmarks of that era was that I would buy screenplay books of films I liked. Of course, we are talking about the last century here, so the films were Reservoir Dogs, Fargo, Sex Lies and Videotape dan yang sewaktu dengannya. I would often buy them second-hand and eschew the ones with too many glossy colour pictures.

Although I am too lazy and non-discriminating to be a real cinephile, those books did help me to know the films better, and to see filmmaking as something I might conceivably do.

When I was based at Indonesia's Miles Films for half of 2004, I was also pleased to see that this company actively published the screenplays of its own films, such as Ada Apa Dengan Cinta? and Eliana, Eliana.

So although, yes, it's part of merchandising and will hardly change the world, Buku Untuk Filem is a series I started because it will help us to know some movies better. And that's surely one of the ways that we can make other, interesting movies later.

The next one after KAMI will be for the film ESTET, written and directed by Mamat Khalid; the book will be edited by Ajami Hashim. It should be out early next year, God willing.

Wednesday, 24 September 2008

Bare behind bars

Bidak di Papan Catur by Raja Petra Kamarudin (Seloka Gelora, 2001, 133 pages).

Any Malaysian dictionary must contain the word ISA, because the Internal Security Act has been such a part of our collective consciousness for decades. The place it has held in our discursive universe has not been static, however.

It has been a bogey, sometimes employed comically to warn you against straying too far from the safe zone. It is the modern-day equivalent of the hantu kopek, the ghost who will crush you in her bosom if you are not home by dusk – although this time, it is the bosom of the State that seeks to keep you close, ostensibly to keep the rest of us safe. It has most likely been a deterrent to some people who would otherwise take part in politics. It may also be a source of pride to others, wherein the devil’s horns magically become a martyr’s halo.

It is to Dr. Mahathir’s credit that he never remanded anyone under the ISA for more than the minimum two years. But our other Prime Ministers have never shown such comparative restraint.

Books written by ISA detainees have become a little subgenre in Malaysian and Singaporean publishing. Highlights would be Aziz Ishak’s Special Guest, Kassim Ahmad’s Universiti Kedua, Syed Husin Ali’s Dua Wajah and Said Zahari’s Dark Clouds at Dawn.

By contrast, Bidak di Papan Catur might seem less substantial. It came out just a few weeks after 10 reformasi activists (including Raja Petra himself) were arrested on April 2001. It consists mainly of affidavits by those men, produced as part of the habeas corpus application for their release.

The ‘instant’ quality of the book means that there is not much opportunity for soul-searching contemplation. But it is precisely this hot-from-the-press factor that makes it so compelling. What it lacks in retrospective insight is made up for in tabloid urgency. (Thankfully, it also eschews poems written in detention).

A few of the other ISA memoirs were written years after the fact, and the distance lent a mellow air to the proceedings. But this book literally begins with a sensational warning – you are about to encounter some obscenity! reader discretion advised! – so you know there ain’t no mellow-mellow.

Raja Petra has said many things about people; people have likewise said many things about him. His style as blogger is flashy, spicy, shot through with contentious vitality. My favourite article of him must be “See you in hell, Muhammad son of Muhammad,” where the former Selangor Menteri Besar is duly knocked down, dragged out and left to hang, probably in that order.

In that piece, I noticed a factual error: A London nightclub is repeatedly referred to as Longfellows, and since such places tend not to be named after poets, I assumed he meant Stringfellows. A pedantic correction, to be sure, but it’s just a hint that his sulphurous broadsides are sometimes best taken with a soupcon of salt. He has a Lenny Bruce quality that certainly was not apparent all those years ago when I read his cycling column in The Star.

This slim book merely confirms what we have long suspected: The interrogations during the initial remand period have nothing to do with the charges that were unofficially laid. The government had accused the detainees of trying to start armed insurrection, but it’s obvious the police were more interested in the inner workings of Opposition parties, especially Keadilan. (In this instance, the detainees included Tian Chua, Ezam Mohd Nor and Hishamuddin Rais). Salacious questions about sexual predilections duly fulfil the ‘warning’ at the book’s beginning.

The book is peppered with domestic photographs of the detainees, to drive home the point that these are ordinary blokes who are now forcibly away from their families. This heart-tugging tactic has always seemed slightly disingenuous: after all, everyone, including the most unrepentant hardcore criminal, has a family.

But the point of the ISA, of course, is that criminality need never be proven. There have been so many cases where the justifications are bogus that it is now an ineffectual bogey: a flat-chested hantu kopek. So many of the most interesting Malaysians have been detained under it, anyway. Whatever paranoia and dread we may have harboured about it have since been locked up – with the key thrown away. It no longer creates fear but heroes.

(Malay Mail, 24 September 2008)

Any Malaysian dictionary must contain the word ISA, because the Internal Security Act has been such a part of our collective consciousness for decades. The place it has held in our discursive universe has not been static, however.

It has been a bogey, sometimes employed comically to warn you against straying too far from the safe zone. It is the modern-day equivalent of the hantu kopek, the ghost who will crush you in her bosom if you are not home by dusk – although this time, it is the bosom of the State that seeks to keep you close, ostensibly to keep the rest of us safe. It has most likely been a deterrent to some people who would otherwise take part in politics. It may also be a source of pride to others, wherein the devil’s horns magically become a martyr’s halo.

It is to Dr. Mahathir’s credit that he never remanded anyone under the ISA for more than the minimum two years. But our other Prime Ministers have never shown such comparative restraint.

Books written by ISA detainees have become a little subgenre in Malaysian and Singaporean publishing. Highlights would be Aziz Ishak’s Special Guest, Kassim Ahmad’s Universiti Kedua, Syed Husin Ali’s Dua Wajah and Said Zahari’s Dark Clouds at Dawn.

By contrast, Bidak di Papan Catur might seem less substantial. It came out just a few weeks after 10 reformasi activists (including Raja Petra himself) were arrested on April 2001. It consists mainly of affidavits by those men, produced as part of the habeas corpus application for their release.

The ‘instant’ quality of the book means that there is not much opportunity for soul-searching contemplation. But it is precisely this hot-from-the-press factor that makes it so compelling. What it lacks in retrospective insight is made up for in tabloid urgency. (Thankfully, it also eschews poems written in detention).

A few of the other ISA memoirs were written years after the fact, and the distance lent a mellow air to the proceedings. But this book literally begins with a sensational warning – you are about to encounter some obscenity! reader discretion advised! – so you know there ain’t no mellow-mellow.

Raja Petra has said many things about people; people have likewise said many things about him. His style as blogger is flashy, spicy, shot through with contentious vitality. My favourite article of him must be “See you in hell, Muhammad son of Muhammad,” where the former Selangor Menteri Besar is duly knocked down, dragged out and left to hang, probably in that order.

In that piece, I noticed a factual error: A London nightclub is repeatedly referred to as Longfellows, and since such places tend not to be named after poets, I assumed he meant Stringfellows. A pedantic correction, to be sure, but it’s just a hint that his sulphurous broadsides are sometimes best taken with a soupcon of salt. He has a Lenny Bruce quality that certainly was not apparent all those years ago when I read his cycling column in The Star.

This slim book merely confirms what we have long suspected: The interrogations during the initial remand period have nothing to do with the charges that were unofficially laid. The government had accused the detainees of trying to start armed insurrection, but it’s obvious the police were more interested in the inner workings of Opposition parties, especially Keadilan. (In this instance, the detainees included Tian Chua, Ezam Mohd Nor and Hishamuddin Rais). Salacious questions about sexual predilections duly fulfil the ‘warning’ at the book’s beginning.

The book is peppered with domestic photographs of the detainees, to drive home the point that these are ordinary blokes who are now forcibly away from their families. This heart-tugging tactic has always seemed slightly disingenuous: after all, everyone, including the most unrepentant hardcore criminal, has a family.

But the point of the ISA, of course, is that criminality need never be proven. There have been so many cases where the justifications are bogus that it is now an ineffectual bogey: a flat-chested hantu kopek. So many of the most interesting Malaysians have been detained under it, anyway. Whatever paranoia and dread we may have harboured about it have since been locked up – with the key thrown away. It no longer creates fear but heroes.

(Malay Mail, 24 September 2008)

Tuesday, 23 September 2008

Punggok in Pusan

I will be making my first trip to the Pusan International Film Festival on the second day of Hari Raya, Insya-Allah.

I have screened there before (Apa Khabar Orang Kampung last year) but couldn't make it because we were shooting Punggok Rindukan Bulan.

Now, it is Punggok Rindukan Bulan that will be screened. The director Azharr Rudin will be there, too, of course. There will also be some other Malaysian films: Muallaf (Yasmin Ahmad), Sell Out! (Yeo Joon Han) and the world premiere of Cicak-Man 2 (in a special section on Asian super-heroes).

Say kimchi!

Monday, 22 September 2008

Jemputan ke pelancaran buku

Buku Untuk Filem KAMI akan dilancarkan Sabtu ini (27 September).

Tempat: The Annexe, Central Market, KL.

* (dewan sama dengan pameran poster "Wayang Kita-Kita")

Masa: 8-10pm.

* Buku terbitan Matahari Books ini ialah edisi terhad yang mengandungi lakonlayar yang lengkap (termasuk babak-babak yang telah disingkir daripada filem) serta bahan bacaan bonus yang menelusuri pembikinan filem KAMI.

Pembikin filem serta beberapa pemeran utamanya akan hadir.

Kudapan disediakan :-)

Tempat: The Annexe, Central Market, KL.

* (dewan sama dengan pameran poster "Wayang Kita-Kita")

Masa: 8-10pm.

* Buku terbitan Matahari Books ini ialah edisi terhad yang mengandungi lakonlayar yang lengkap (termasuk babak-babak yang telah disingkir daripada filem) serta bahan bacaan bonus yang menelusuri pembikinan filem KAMI.

Pembikin filem serta beberapa pemeran utamanya akan hadir.

Kudapan disediakan :-)

Sunday, 21 September 2008

After the premiere

Thanks to the 200 of you who turned up for the only screenings of the 20 September 2008 version of Malaysian Gods.

I will not show that version again. In fact, the video and audio files for it have already been deleted.

I am instead rewriting it totally for its DVD release, which I tentatively schedule for 1 November :-) I doubt if it will even have five sentences in common with what we screened yesterday. And I think it will end up being around 80 minutes long. (12 minutes longer than the first version).

It will no longer be a one-take but will use only selected clips from the original footage. So, additional scenes will be shot.

This time, I will narrate the thing myself and it will be a nonstop gabfest!

I will not show that version again. In fact, the video and audio files for it have already been deleted.

I am instead rewriting it totally for its DVD release, which I tentatively schedule for 1 November :-) I doubt if it will even have five sentences in common with what we screened yesterday. And I think it will end up being around 80 minutes long. (12 minutes longer than the first version).

It will no longer be a one-take but will use only selected clips from the original footage. So, additional scenes will be shot.

This time, I will narrate the thing myself and it will be a nonstop gabfest!

Friday, 19 September 2008

Wednesday, 17 September 2008

City of mud

Mat Som by Lat (Berita Publishing, 2004 (original edition 1989), 189 pages)

Last week, we looked at A Samad Ismail’s short stories. He was more than just a short-story writer, of course. Rather topically, he was a detainee of the notorious Internal Security Act!

But since we don’t have to be topical, let’s instead check out this book where he makes an appearance. He plays the titular guy’s boss, a crusty but benign newspaper editor.

Unlike his earlier hits Kampung Boy and Town Boy, Lat does not make this story explicitly autobiographical. Mat Som wants to write, not draw. But in some ways it can be seen as a continuation of the earlier two books. The shy but studiously observant narrator is getting used to his surroundings, which have grown from a small village to town (Ipoh) and now KL.

Mat Som (the person) could stand in for any number of young men in Kuala Lumpur with uncertain employment and romantic prospects. And the Kuala Lumpur we see is very much a time-capsule of the 1980s: replete with minibuses, and cameos from the poets and artists who were then active.

Mat Som (the book) is popular but has not become as canonical as the first two books. Is this because people prefer autobiography?

Mat Som struggles to survive as a freelance writer. His father wants him to marry his village play-mate Faridah, whom he has not seen in years. Although chafing at how old-fashioned the idea of an arranged marriage is, he nevertheless agrees to meet her. In the meantime, he is also mildly flirting with his comely neighbour Yam.

Set during the course of only a few days, the book is beefed out with flashbacks to Mat Som’s village boyhood. The trigger for the memories always seems to be water, whether it’s a mad downpour or a decadent swimming-pool. Perhaps looking at the clearness of water is a way to escape from the mud of city life.

To the uninitiated, it might seem odd that Mat Som’s circle of friends is much more mono-racial than what Lat represented in Town Boy. Was Ipoh in the 1960s a more culturally diverse place than KL in the 80s?

Then again, Lat’s work is here is descriptive rather then prescriptive. Politically, Mat Som can be reminded that he is a ‘prince of the land.’ In all other respects, this does not hold true; his visit to his father’s depressing workplace confirms this.

One of the loveliest images here is of him and Yam having late-night sup kambing at a stall, under a makeshift awning of an old Hindi movie poster painted on cloth. The movie is Hamraaz (1967), a glamorous murder mystery set among the rich and famous. The two people under the cloth are being temporarily sheltered by this fantasy world.

He’s indignant when Tanjung Malim, in some ways the birthplace of the Malay intelligentsia, is casually insulted by big-city kids on a train-stop. But what are his other political views? He existed at a time when there did not seem to be much choice, as the BN establishment was so entrenched. Oppositional discourse didn’t yet find a way to include the many people like him. But if this were set just a decade later, I wonder if he would have attended reformasi demonstrations, and why.

In him, the values of the village and the city struggle to reconcile. We see this most explicitly in the closing scene. He has just served as best man at a friend’s wedding, and is still in formal baju Melayu. Yam, who is in jeans, takes him along to an unknown destination.

It turns out to be a rock concert. The rockers in their skin-tight gear snigger at his incongruous attire. But he learns to enjoy it, by standing in the wings with Yam. The fact that he’s in the wings is as significant as the urban-rural juxtaposition he visually represents. He is, in a sense, waiting for his turn to get on stage.

When reviewing this book in 1989, Kee Thuan Chye was disappointed that it was not a tougher social critique. He thought the ending promised something more, and expected a sequel. Lat has not come up with one and I don’t know if he intends to.

But in the meantime, thousands of Mat Soms are walking and dreaming around you today. Only the mat rempit among them get their stories told easily. But the rest will have their say.

(Malay Mail, 17 September 2008)

Saturday, 13 September 2008

Thursday, 11 September 2008

Malaysiakini on "Malaysian Gods"

'Malaysian Gods': Revisiting Sept 20

by Andrew Ong | Sep 11

Malaysiakini

All eyes are on Sept 16 where the winds of change are expected to blow away the ruling coalition from the corridors of power... or at least this is what opposition stalwart Anwar Ibrahim and his supporters claim.

But how many of us remember Sept 20, 1998? This was the date which witnessed the birth of a massive political awakening.

On this fateful day, tens of thousands of people took to the streets in Kuala Lumpur to usher in what will later be known as the 'reformasi' movement.

Controversial film producer Amir Muhammad retraces the events in his latest offering, Malaysian Gods.

"Malaysian Gods is something I made to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Sept 20, 1998 anti-government demonstration in KL.

"The title was chosen because we in Malaysia have a bad habit of treating our politicians like gods. So this is an ironic reference to that. It is certainly not political propaganda but more of a celebration of spaces, including democratic space," he told Malaysiakini.

"What was significant (during the time) was the numbers (who attended the demonstrations). People were collectively just shocked by a lot of things at the time, and they choose to express that shock and outrage in one go," he added.

The 68-minute film begins with an unnamed narrator walking along the same path that the demonstration took, from Masjid Negara to PWTC.

"It starts to rain but he continues walking. He starts to not only reminisce about the demonstration, but to ponder the buildings and people around him," explained Amir.

There are no actors or interviews in the film. Neither is the infamous archive footage of riot police battering hapless protestors used.

"It is not a conventional movie. It has elements of an experimental video, documentary and fiction. I thought it would be more interesting if the narrator was one fictional character whose impressions are made up of a lot of personalities," he added.

Though the film surrounds the tumultuous periods of rowdy street demonstrations, Amir denies that he is attempting to glorify demonstrations or mob rule.

"I think street demonstrations are a vital part of democracy, but it’s different from mob rule. A government can still be one that consists of mob rule even if it bans street demonstrations," he explained.

Unlike his previous movies such as Lelaki Komunis Terakhir and Apa Khabar Orang Kampung, Malaysian Gods had no problems with the Censorship Board and was given the green light on Sept 5, three weeks after submission.

According to Amir, the film cost a modest RM10,000 to make and is produced by independent production house Da Huang Pictures. The film also marks the debut of prominent lawyer Malik Imtiaz Sarwar in the film industry as he is credited as an executive producer.

Screening would be on Sept 20 at GSC 1-Utama, Selangor at 5pm, 7pm and 9pm for one day only. Those who miss it would have to wait for the DVD release later this year.

by Andrew Ong | Sep 11

Malaysiakini

All eyes are on Sept 16 where the winds of change are expected to blow away the ruling coalition from the corridors of power... or at least this is what opposition stalwart Anwar Ibrahim and his supporters claim.

But how many of us remember Sept 20, 1998? This was the date which witnessed the birth of a massive political awakening.

On this fateful day, tens of thousands of people took to the streets in Kuala Lumpur to usher in what will later be known as the 'reformasi' movement.

Controversial film producer Amir Muhammad retraces the events in his latest offering, Malaysian Gods.

"Malaysian Gods is something I made to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Sept 20, 1998 anti-government demonstration in KL.

"The title was chosen because we in Malaysia have a bad habit of treating our politicians like gods. So this is an ironic reference to that. It is certainly not political propaganda but more of a celebration of spaces, including democratic space," he told Malaysiakini.

"What was significant (during the time) was the numbers (who attended the demonstrations). People were collectively just shocked by a lot of things at the time, and they choose to express that shock and outrage in one go," he added.

The 68-minute film begins with an unnamed narrator walking along the same path that the demonstration took, from Masjid Negara to PWTC.

"It starts to rain but he continues walking. He starts to not only reminisce about the demonstration, but to ponder the buildings and people around him," explained Amir.

There are no actors or interviews in the film. Neither is the infamous archive footage of riot police battering hapless protestors used.

"It is not a conventional movie. It has elements of an experimental video, documentary and fiction. I thought it would be more interesting if the narrator was one fictional character whose impressions are made up of a lot of personalities," he added.

Though the film surrounds the tumultuous periods of rowdy street demonstrations, Amir denies that he is attempting to glorify demonstrations or mob rule.

"I think street demonstrations are a vital part of democracy, but it’s different from mob rule. A government can still be one that consists of mob rule even if it bans street demonstrations," he explained.

Unlike his previous movies such as Lelaki Komunis Terakhir and Apa Khabar Orang Kampung, Malaysian Gods had no problems with the Censorship Board and was given the green light on Sept 5, three weeks after submission.

According to Amir, the film cost a modest RM10,000 to make and is produced by independent production house Da Huang Pictures. The film also marks the debut of prominent lawyer Malik Imtiaz Sarwar in the film industry as he is credited as an executive producer.

Screening would be on Sept 20 at GSC 1-Utama, Selangor at 5pm, 7pm and 9pm for one day only. Those who miss it would have to wait for the DVD release later this year.

Siput Serawak was a lady with an attitude

Oh, I just love her!

One of my favourite old-movie anecdotes, as related by the late scriptwriter Hamzah Hussin, was about her. She once came up to him during lunch-time and said, "Hamzah, jom makan!" And he said, "Mana boleh, Siput? Sekarang bulan puasa." So she lifted up her dress (she had no underwear) and flashed him, and then said, "Dah batal puasa kau. Jom makan!"

And yes her name really was spelled like that. It was her daughter Anita who changed it to Sarawak.

One of my favourite old-movie anecdotes, as related by the late scriptwriter Hamzah Hussin, was about her. She once came up to him during lunch-time and said, "Hamzah, jom makan!" And he said, "Mana boleh, Siput? Sekarang bulan puasa." So she lifted up her dress (she had no underwear) and flashed him, and then said, "Dah batal puasa kau. Jom makan!"

And yes her name really was spelled like that. It was her daughter Anita who changed it to Sarawak.

Wednesday, 10 September 2008

Samad goes to heaven

Ingin Jadi Pujangga by A. Samad Ismail (Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 1994, 833 pages)

When I heard the news of A Samad Ismail’s passing on Thursday night, just one sentence came to mind: “Matinya pun pada malam Jumaat!”

(For the sake of clarity, I should point out that malam Jumaat means Thursday night, and is considered holy. So to die on a Thursday night is, in the Malay-Muslim scheme of things, a blessed thing).

The sentence isn’t mine but his. It’s the closing line of one of his greatest short stories. Make no mistake: Although he was known primarily as a journalist, he was also one of our finest short-story writers.

So to commemorate him, I took down this hardcover book and re-read some pieces. Ingin Jadi Pujangga collects 40 of his stories from 1944-91. The first that I headed to was “Ah Khaw Masuk Syurga” (1960), which is where the sentence came from.

The titular fellow is Chinese (you don’t say!) but is being sheltered by a Malay family to escape Japanese detection. It’s narrated by the youngest son of the house. Ah Khaw, who is in his 50s, is made to wear baju Melayu and songkok to pass as Malay. But the narrator’s mother gets it into her head that he should convert to Islam, too.

She insists because she cares about him, and she wants to see him saved in not only this world but the next. But the narrator’s older brother will have none of it, accusing her of being a sanctimonious bully. He asks: Isn’t Ah Khaw’s opium addiction a greater problem than his uncircumcised status?

The mother’s piety is really a form of narrow sentimentality, but her honest optimism makes a nice contrast to her older son’s brusque pragmatism. You could say the story is about a clash of values, but its brilliance comes from the fact that the characters are never just their viewpoints. You can actually see and hear them.

Decades before the phrase ‘inter-faith’ invaded our news, this story sets out potential grounds for conflict but does it with an earthy humour that subtly undermines any rigid sectarianism.

The Introduction states that this story was actually written hastily because Samad needed to fill a blank space in a newspaper he was editing. Ah, if only all of us could think so creatively ‘on the typewriter!’

This brings us to “Ingin Jadi Pujangga” (1951), a marvelous satire of a wannabe intellectual, Arif, who’s trying to write a short story. With his head chock-full of noble slogans and ideals, he tries to block out the mundane minutae of his domestic and working life to compose something. The story he’s writing – about Mariati, a selfless, thrifty heroine with a penchant for classical music – is perfectly ridiculous, but he doesn’t realize this since he’s too busy trying to use fancy (and preferably Indonesian-derived) words so that he can be taken seriously as a philosophical writer.

His high-minded ruminations collide hilariously with the crude reality around him. When he accuses his wife of spending too much, she snaps back that every cent he’s given her has now been excreted from his and their children’s bowels. No wonder he seeks refuge in Mariati instead!

Arif, you gather, is not an artist because he’s not honest or imaginative enough to take in his life and surroundings and make something of them. But the fun that the writer has with him is tinged with affection – there are worse things than intellectual pretensions, after all.

This short story was actually smuggled out of prison and published under a pseudonym. (There were several others and some are still lost because Samad used so many pseudonyms that it became difficult to keep track). It became very popular. Many people tried to copy the style but no one else could get that wry but hearty tone right.

Malay fiction since the 1970s became more solemn and didactic; in other words, it got worse. Reading these stories will energise you. How could they not? Samad relished life – and experienced so much of it – that his words had a throbbing, unfussy vitality.

Although I met him once, I can’t claim enough of an acquaintanceship to regale you with colourful anecdotes. But the best way to remember a writer is to go back to his books, anyway – and that’s something you can do any day of the week.

(Malay Mail, 10 September 2008)

When I heard the news of A Samad Ismail’s passing on Thursday night, just one sentence came to mind: “Matinya pun pada malam Jumaat!”

(For the sake of clarity, I should point out that malam Jumaat means Thursday night, and is considered holy. So to die on a Thursday night is, in the Malay-Muslim scheme of things, a blessed thing).

The sentence isn’t mine but his. It’s the closing line of one of his greatest short stories. Make no mistake: Although he was known primarily as a journalist, he was also one of our finest short-story writers.

So to commemorate him, I took down this hardcover book and re-read some pieces. Ingin Jadi Pujangga collects 40 of his stories from 1944-91. The first that I headed to was “Ah Khaw Masuk Syurga” (1960), which is where the sentence came from.

The titular fellow is Chinese (you don’t say!) but is being sheltered by a Malay family to escape Japanese detection. It’s narrated by the youngest son of the house. Ah Khaw, who is in his 50s, is made to wear baju Melayu and songkok to pass as Malay. But the narrator’s mother gets it into her head that he should convert to Islam, too.

She insists because she cares about him, and she wants to see him saved in not only this world but the next. But the narrator’s older brother will have none of it, accusing her of being a sanctimonious bully. He asks: Isn’t Ah Khaw’s opium addiction a greater problem than his uncircumcised status?

The mother’s piety is really a form of narrow sentimentality, but her honest optimism makes a nice contrast to her older son’s brusque pragmatism. You could say the story is about a clash of values, but its brilliance comes from the fact that the characters are never just their viewpoints. You can actually see and hear them.

Decades before the phrase ‘inter-faith’ invaded our news, this story sets out potential grounds for conflict but does it with an earthy humour that subtly undermines any rigid sectarianism.

The Introduction states that this story was actually written hastily because Samad needed to fill a blank space in a newspaper he was editing. Ah, if only all of us could think so creatively ‘on the typewriter!’

This brings us to “Ingin Jadi Pujangga” (1951), a marvelous satire of a wannabe intellectual, Arif, who’s trying to write a short story. With his head chock-full of noble slogans and ideals, he tries to block out the mundane minutae of his domestic and working life to compose something. The story he’s writing – about Mariati, a selfless, thrifty heroine with a penchant for classical music – is perfectly ridiculous, but he doesn’t realize this since he’s too busy trying to use fancy (and preferably Indonesian-derived) words so that he can be taken seriously as a philosophical writer.

His high-minded ruminations collide hilariously with the crude reality around him. When he accuses his wife of spending too much, she snaps back that every cent he’s given her has now been excreted from his and their children’s bowels. No wonder he seeks refuge in Mariati instead!

Arif, you gather, is not an artist because he’s not honest or imaginative enough to take in his life and surroundings and make something of them. But the fun that the writer has with him is tinged with affection – there are worse things than intellectual pretensions, after all.

This short story was actually smuggled out of prison and published under a pseudonym. (There were several others and some are still lost because Samad used so many pseudonyms that it became difficult to keep track). It became very popular. Many people tried to copy the style but no one else could get that wry but hearty tone right.

Malay fiction since the 1970s became more solemn and didactic; in other words, it got worse. Reading these stories will energise you. How could they not? Samad relished life – and experienced so much of it – that his words had a throbbing, unfussy vitality.

Although I met him once, I can’t claim enough of an acquaintanceship to regale you with colourful anecdotes. But the best way to remember a writer is to go back to his books, anyway – and that’s something you can do any day of the week.

(Malay Mail, 10 September 2008)

Tuesday, 9 September 2008

Saturday, 6 September 2008

'Malaysian Gods' screening details

It will be screened for only one day, Saturday 20 September.

This is because 20 September happens to be the 10th anniversary of the demonstration that it talks about.

The venue: GSC 1 Utama.

I knew I wanted it to screen in a public space – that is, a real cinema. We initially thought that if we booked the cinema for a 'private viewing', we wouldn't need to go through censorship. But it turns out we still needed a censorship certificate. And yesterday, luckily, we got it! (Although the censors took three weeks to get back to us, which is longer than the norm).

So come along and enjoy the show.

Don't expect agitprop! It's quite a chill-out piece and is about several types of spaces, not just the democratic one. Since I no longer live in KL (not that PJ is far away lah), I also wanted to sum up what I felt about the city of my birth and upbringing. Yes, it also has a twist ending – but perhaps not of the Susuk variety.

There are 3 screenings and they can be purchased now: 5pm, 7pm, and 9pm.

Each screening is limited to 90 people.

This is because 20 September happens to be the 10th anniversary of the demonstration that it talks about.

The venue: GSC 1 Utama.

I knew I wanted it to screen in a public space – that is, a real cinema. We initially thought that if we booked the cinema for a 'private viewing', we wouldn't need to go through censorship. But it turns out we still needed a censorship certificate. And yesterday, luckily, we got it! (Although the censors took three weeks to get back to us, which is longer than the norm).

So come along and enjoy the show.

Don't expect agitprop! It's quite a chill-out piece and is about several types of spaces, not just the democratic one. Since I no longer live in KL (not that PJ is far away lah), I also wanted to sum up what I felt about the city of my birth and upbringing. Yes, it also has a twist ending – but perhaps not of the Susuk variety.

There are 3 screenings and they can be purchased now: 5pm, 7pm, and 9pm.

Each screening is limited to 90 people.

Friday, 5 September 2008

Video column

I begin a lo-fi video column called, erm, Amir's Alphabet today! It will be published every other Friday at this highly recommended new site called The Nut Graph. It's the only column that promises to never mention a single politician.

The first one is E for Egg.

Thursday, 4 September 2008

Postal pre-orders!

You can now pre-order Buku Untuk Filem KAMI.

The price is RM30 (free shipping anywhere in Malaysia).

Each book is numbered from 1 to 1,000. I am reserving the first five for the film's screenwriter, co-director, producer as well as the book's editor and designer. So #6 onwards will be on sale. (I myself aim to keep only #1,000).

Each pre-ordered book will be autographed by the screenwriter and co-director Fariza Azlina Isahak, and the book's editor Ahmad Kamal Abu Bakar. If you'd like a dedication, let us know what name to put there lah.

Pre-orders will run for 3 weeks, until 25 September. The pre-ordered books will be posted on 27 September. After that, the book will be sent to selected bookstores.

Kindly dump the money to Maybank account 014105120512 (Amir Muhammad) and email your confirmation as well as postal address to matahari.books@gmail.com .

Thanks mucho :-)

The price is RM30 (free shipping anywhere in Malaysia).

Each book is numbered from 1 to 1,000. I am reserving the first five for the film's screenwriter, co-director, producer as well as the book's editor and designer. So #6 onwards will be on sale. (I myself aim to keep only #1,000).

Each pre-ordered book will be autographed by the screenwriter and co-director Fariza Azlina Isahak, and the book's editor Ahmad Kamal Abu Bakar. If you'd like a dedication, let us know what name to put there lah.

Pre-orders will run for 3 weeks, until 25 September. The pre-ordered books will be posted on 27 September. After that, the book will be sent to selected bookstores.

Kindly dump the money to Maybank account 014105120512 (Amir Muhammad) and email your confirmation as well as postal address to matahari.books@gmail.com .

Thanks mucho :-)

Sample pages

This book was laid out by the cute young things of Bright Lights at Midnight (who also did New Malaysian Essays 1).

Wednesday, 3 September 2008

It takes a village

THE KAMPUNG BOY by Lat (Berita Publishing, 1979, 144 pages)

Another newspaper (which certainly is not called The Moon) recently ran a sprawling piece in which its writers recommended 51 books to be read on the occasion of our 51st Merdeka Day. Seeing as how we were having a long weekend, I was looking forward to some recommendations myself.

So I started reading the capsule descriptions. But it didn’t take long to notice there was something funny about the list, in both senses of the word ‘funny.’ Every single one of the 51 books was foreign. And this was pumped as some kind of Merdeka special?

Lest I be mistaken for the kind of demagogue who’d want to ban an Avril Lavigne concert, let me say that I am a big fan of foreigners, the sexier the better. But for a whole bunch of presumably educated locals to not be able to recommend a single local book for an Independence spread is, to use that word again, funny.

So I’d like to talk about – and recommend – a much-loved Malaysian book. It’s so famous that it needs no introduction, but I am going to give it one anyway. This was the first book by a man who joined The New Straits Times initially as a crime reporter, before his talents were better-used in another capacity.

The Kampung Boy takes us back to the village where Lat grew up. The “graphic novel” (although the term was not used then) spills over with life and laughter. Even the shape of the Lat books (slightly shorter than a standard paperback but much longer) has a panoramic generosity.

Your eyes roam around the page at leisure, picking out details. It had been maybe two decades since I’d last read it, but I was pleasantly surprised to see how many of the images have stayed with me: the religious teacher’s rattan cane, the father’s sarong slipping off after his Tarzan impersonation, the younger sibling being taxied in a pinang spathe.

There were others that I probably didn’t catch before, such the drunken man hiccupping next to the tea-stall (in front of the mosque, mind you!)

This is art that is transparent; nothing is shoved in your face. The adolescent terrors (irate parents, ‘monster’ tin dredges) and joys (food, camadarerie with the Meor brothers) are sculpted, as it were, out of light. He was only 28 when he published this, so the nostalgia isn’t of the fuzzy but concrete and lively variety.

And it isn’t all rosy, either. The book ends with the possibility of the boy’s promised ‘property’ being sold off so that the family can move to the town. The tin-mining company that wants to buy the land is also the same one that sent the police after the boys who illegally panned in the wake of the dredges.

One can write a paper with the words ‘Malay identity’, ‘modernity’ and ‘capitalism’ about this particular theme. But the final wordless image of this book can say just as much and cause a little heartbreak along the way: We are inside the bus as it pulls away on a journey to boarding school, the boy is waving (we don’t see his face so we don’t know if the excitement outweighs the sadness) and the father is counting money in his wallet. They are also sitting in the back rather than front of the bus, which can either denote lower social status or be a complete coincidence.

The foreground cast is not as ‘multi-racial’ as in the later urban cartoons, but this never makes the book parochial. Rather, it’s the intimate and culturally specific details, shared with such generosity and warmth, that make it a classic. Like Adibah Amin, Lat is so secure in his own identity that when he looks at others he does not see threats, only opportunities to observe and learn.

The tone of the narration is kept as clear as the kampung river must have been. But no river is tranquil for long, as there’s always a naked adolescent waiting to jump in. So, too, does Lat’s impish pen frequently open up satirical possibilities that he would exploit further in his work.

Decades before its international success (the Japanese, French and German translations; the TV series; the plug from Matt Groening), The Kampung Boy spoke first to us. And it will continue to do so for as long as we think of home.

(Malay Mail, 3 September 2008)

Tuesday, 2 September 2008

Coming soon from Matahari Books

Buku Untuk Filem is a series of limited-edition (and numbered!) books to accompany selected Malaysian films. Each book will be released just as the film comes out.

The book will have the complete screenplay (with scenes that were dropped from the final film) as well as bonus stuff like essays and interviews. It is a large-format paperback (20.5 cm tall and 25.5 cm wide).

The main fun for me is to match each film with a book editor whom I think can do it justice.

Series Title: BUKU UNTUK FILEM

Title: KAMI

Screenwriter: Fariza Azlina Isahak

Book Editor: Ahmad Kamal Abu Bakar

Length: 156 pages

ISBN: 983-43596-3-8

Price: RM30

Print run is 1,000 copies. No reprints.

Images from the book will be posted soon. In the meantime, this is the trailer for the film, which comes out 1 October:

Rokenrol!

The book will have the complete screenplay (with scenes that were dropped from the final film) as well as bonus stuff like essays and interviews. It is a large-format paperback (20.5 cm tall and 25.5 cm wide).

The main fun for me is to match each film with a book editor whom I think can do it justice.

Series Title: BUKU UNTUK FILEM

Title: KAMI

Screenwriter: Fariza Azlina Isahak

Book Editor: Ahmad Kamal Abu Bakar

Length: 156 pages

ISBN: 983-43596-3-8

Price: RM30

Print run is 1,000 copies. No reprints.

Images from the book will be posted soon. In the meantime, this is the trailer for the film, which comes out 1 October:

Rokenrol!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)